John “Jack” Silas Reed died 100 years ago. A journalist, poet and fervent communist, he reported some of the events that shook the world in the early XX century.

Reed was born on October 22, 1887 to an upper-middle class family in Portland (US West Coast). On his father’s insistence, he went to study at Harvard, where he got involved with student groups and had his first contacts with socialism.

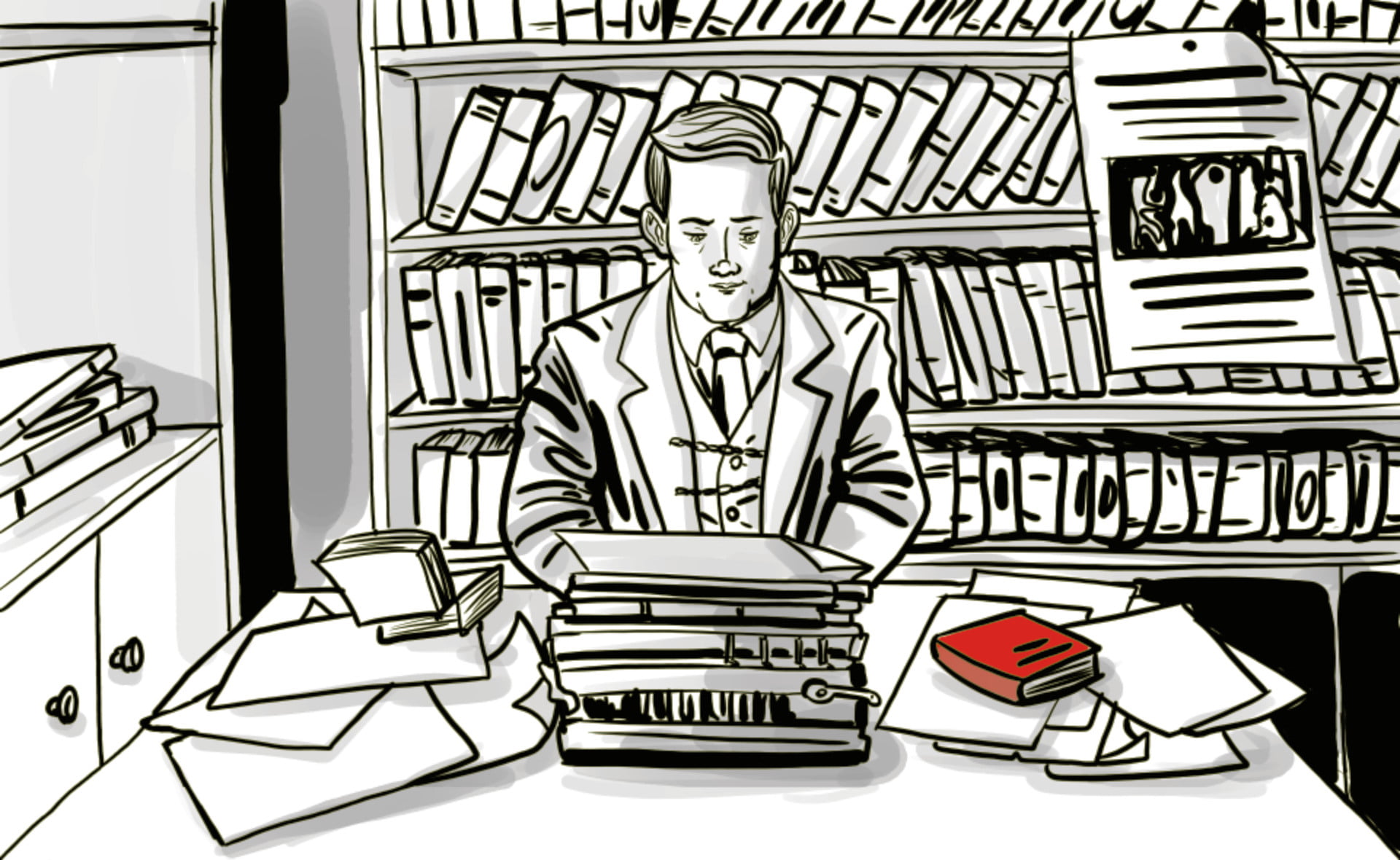

After some time traveling, Reed established himself as a freelance journalist in New York, contributing pieces to several outlets and magazines. His coverage and participation in worker strikes during this vibrant time helped consolidate his political views.

Nevertheless, it was his work covering events outside the United States that would become renowned. In 1913, the Metropolitan magazine sent him to Mexico to cover the Mexican Revolution.

Insurgent Mexico

John Reed spent four months with the revolutionary army of Pancho Villa in northern Mexico, and he was a witness to the important victory at Torreón. The stories he telegraphed would make up his book “Insurgent Mexico.”

As a young and tall American, Reed was hard pressed to go unnoticed. But for weeks he ate, drank, shared stories and faced the same dangers as the foot soldiers of the so-called “Northern Division.” While anecdotes and personal stories were always plentiful, he never lost sight of who were the real protagonists of the story he was telling.

John Reed never hid which side of the story he identified with, and deserves credit for the fact that it did not make his writing biased. At the same time, he was careful not to overstate the epic events he was witnessing, always keeping a certain lightness and even humor in his tone. This style was in full display in this excerpt on Villa’s taking of Ciudad Juárez:

“Villa found that he hadn’t enough trains to carry all his soldiers, even when he had ambushed and captured a Federal troop train, sent south by General Castro, the Federal commander in Juarez. So he telegraphed that gentleman as follows, signing the name of the Colonel in command of the troop train:

Engine broken down at Moctezuma. Send another engine and five cars.

The unsuspecting Castro immediately dispatched a new train. Villa then telegraphed him:

Wires cut between here and Chihuahua. Large force of rebels approaching from south. What shall I do?

Castro replied: Return at once.

And Villa obeyed, telegraphing cheering messages at every station along the way. The Federal commander got wind of his coming about an hour before he arrived, and left, without informing his garrison, so that, outside of a small massacre, Villa took Juarez almost without a shot.”

With good journalistic instincts, Reed could foresee that differences were emerging between Villa and the Mexican constitutionalist leaders, Venustiano Carranza chief among them. However, Villa’s loyalty made him contemplate the mere doubt as an affront. History would show that Reed’s doubts were well founded.

Anti-war activist

In 1914, Reed was sent to Europe to cover the First World War. In France, he grew frustrated by censorship and the impossibility to report from the front, and was luckier in Eastern Europe.

Nevertheless, the young American was very concerned to see how nationalism was trumping working class solidarity amidst the collapse of the Second International. There was no clearer example than Germany, and Reed had the chance to visit Berlin and talk to Karl Liebknecht, one of the few anti-war voices in the German left.

Although Liebknecht did not say much in the interview, Reed would write on the subject years later.

“But it was the Ebert-Scheidemann Government, the Kaiser Socialists, so long detested by the Allied capitalist press—who by suppressing the revolt of the German working-class with the aid of the Kaiser’s troops, allowed that mob to shoot holes in Karl Liebknecht’s back and trample the life out of Rosa Luxemburg. And the Allied capitalist press applauds…”

Back in the US, Reed met Louise Bryant, who became his companion in life and struggle. His activity was now geared towards opposing the US entry in the war, which Woodrow Wilson declared in April 1917. Horrified by the pro-war spirit in US society, Bryant and Reed left the country months later… for Petrograd.

Ten days that shook the world

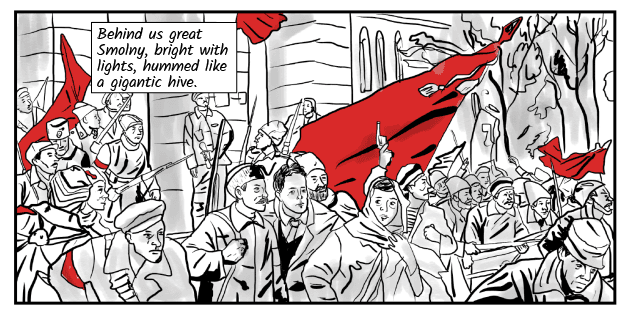

John Reed’s “immortal” work was the one he wrote in the final months of 1917. In Petrograd, he was a first hand witness of the October Revolution, and his book “Ten Days that Shook the World” remains one of the most essential accounts of this time. Lenin himself called it “a truthful and most vivid exposition” of the Revolution.

In the old capital of the Russian Empire, Reed had a front row seat to some extraordinary events. He witnessed the exhaustion and decay of Kerensky’s provisional government, the devastating effects of the war, and the rise of the Bolsheviks, especially in the Petrograd Soviet. The US journalist reported on the heated debates and the construction of a majority, until Lenin’s return brought the decisive guidance towards the Bolshevik triumph with the storming of the Winter Palace on November 7, 1917.

In these words, Reed is unable to hide his excitement and his grasp of the magnitude of what he had just witnessed:

“So. Lenin and the Petrograd workers had decided on insurrection, the Petrograd Soviet had overthrown the Provisional Government, and thrust the coup d’etat upon the Congress of Soviets. Now there was all great Russia to win – and then the world!”

Reed’s testimony offered a unique window into the weeks following the October triumph, narrating the struggles and counter-revolutionary threats, as well as the tremendous enthusiasm all around. He also provided an up close and personal view of Lenin, the historic leader of the Russian Revolution:

“It was just 8:40 when a thundering wave of cheers announced the entrance of the presidium, with Lenin—great Lenin—among them. Unimpressive, to be the idol of a mob, loved and revered as perhaps few leaders in history have been. A strange popular leader—a leader purely by virtue of intellect; colourless, humourless, uncompromising and detached, without picturesque idiosyncrasies—but with the power of explaining profound ideas in simple terms, of analysing a concrete situation. And combined with shrewdness, the greatest intellectual audacity.”

Reed returned to the United States in April 1918, but was constantly persecuted by the US justice system for his opposition to the war and support for the Bolsheviks. Two years later he returned to Petrograd, after a troubled trip that saw him detained in Finland for months. Now working in the Comintern, his mission was to establish a Communist Party in the US. But with his health suffering, he contracted typhus and died on October 17, 1920. He was just 32 years-old.

John Reed was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis alongside other heroes of the Revolution. It was an honor and a proper recognition of his revolutionary internationalism.

Text: Ricardo Vaz. Illustrations: César Mosquera.