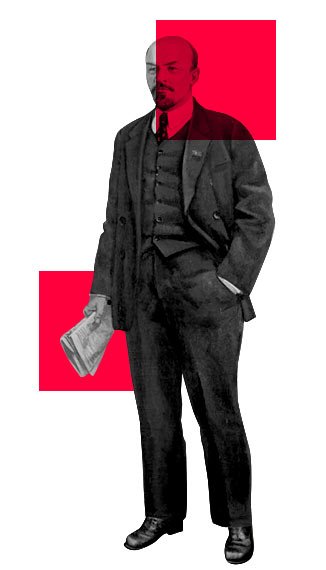

Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) fue un estudiante brillante y líder político precoz, se sumaría al Partido Obrero Socialdemócrata de Rusia. Lenin llevaba el periódico del partido (Iskra) y más tarde vendría a dirigir la fracción mayoritaria – bolchevique. Con una constante actividad política y producción teórica voraz, la oposición de Lenin al régimen zarista le forzaría a largos períodos en el exilio, lo que no le impediría jugar un papel clave en los acontecimientos. En el período convulsionado que siguió a la caída del zar con la Revolución de Febrero de 1917, fue el liderazgo de Lenin el que llevó al Partido Bolchevique, minoritario en ese momento, a dirigir y ejecutar el episodio que marca un antes y un después en la historia de la Humanidad – la Revolución de Octubre. Durante los años anteriores a la Revolución de Octubre, Lenin reflexionó mucho sobre la importancia de la comunicación y la propaganda. A continuación reproducimos un fragmento de «Nuestra tarea inmediata», artículo publicado originalmente en Rabochaya Gazeta en 1899.

ABRE COMILLAS

We are all agreed that our task is that of the organisation of the proletarian class struggle. But what is this class struggle? When the workers of a single factory or of a single branch of industry engage in struggle against their employer or employers, is this class struggle? No, this is only a weak embryo of it. The struggle of the workers becomes a class struggle only when all the foremost representatives of the entire working class of the whole country are conscious of themselves as a single working class and launch a struggle that is directed, not against individual employers, but against the entire class of capitalists and against the government that supports that class. Only when the individual worker realises that he is a member of the entire working class, only when he recognises the fact that his petty day-to-day struggle against individual employers and individual government officials is a struggle against the entire bourgeoisie and the entire government, does his struggle become a class struggle. “Every class struggle is a political struggle”[1]—these famous words of Marx are not to be understood to mean that any struggle of workers against employers must always be a political struggle. They must be understood to mean that the struggle of the workers against, the capitalists inevitably becomes a political struggle insofar as it becomes a class struggle. It is the task of the Social-Democrats, by organising the workers, by conducting propaganda and agitation among them, to turn their spontaneous struggle against their oppressors into the struggle of the whole class, into the struggle of a definite political party for definite political and socialist ideals. This is some thing that cannot be achieved by local activity alone.

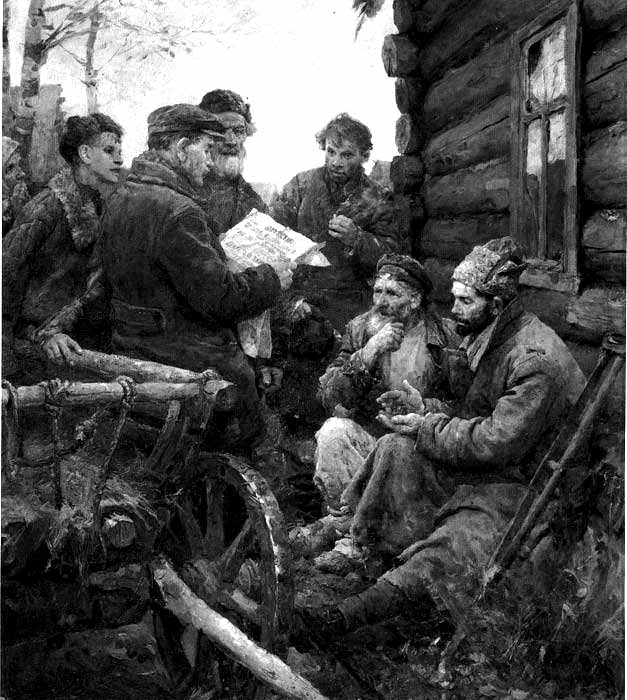

LocalSocial-Democratic activity has attained a fairly high level in our country. The seeds of Social-Democratic ideas have been broadcast throughout Russia; workers’ leaf lets—the earliest form of Social-Democratic literature—are known to all Russian workers from St. Petersburg to Krasnoyarsk, from the Caucasus to the Urals. All that is now lacking is the unification of all this local work into the work of a single party. Our chief drawback, to the overcoming of which we must devote all our energy, is the narrow “amateurish” character of local work. Because of this amateurish character many manifestations of the working-class movement in Russia remain purely local events and lose a great deal of their significance as examples for the whole of Russian Social-Democracy, as a stage of the whole Russian working-class movement. Because of this amateurishness, the consciousness of their community of interests throughout Russia is insufficiently inculcated in the workers, they do not link up their struggle sufficiently with the idea of Russian socialism and Russian democracy. Because of this amateurishness the comrades’ varying views on theoretical and practical problems are not openly discussed in a central newspaper, they do not serve the purpose of elaborating a common programme and devising common tactics for the Party, they are lost in narrow study-circle life or they lead to the inordinate exaggeration of local and chance peculiarities. Enough of our amateurishness! We have attained sufficient maturity to go over to common action, to the elaboration of a common Party programme, to the joint discussion of our Party tactics and organisation.

Russian Social-Democracy has done a great deal in criticising old revolutionary and socialist theories; it has not limited itself to criticism and theorising alone; it has shown that its programme is not hanging in the air but is meeting the extensive spontaneous movement among the people, that is, among the factory proletariat. It has now to make the following, very difficult, but very important, step—to elaborate an organisation of the movement adapted to our conditions. Social-Democracy is not confined to simple service to the working-class movement: it represents “the combination of socialism and the working-class movement” (to use Karl Kautsky’s definition which repeats the basic ideas of the Communist Manifesto); the task of Social-Democracy is to bring definite socialist ideals to the spontaneous working-class movement, to connect this movement with socialist convictions that should attain the level of contemporary science, to connect it with the regular political struggle for democracy as a means of achieving socialism—in a word, to fuse this spontaneous movement into one indestructible whole with the activity of the revolutionary party. The history of socialism and democracy in Western Europe, the history of the Russian revolutionary movement, the experience of our working-class movement—such is the material we must master to elaborate a purposeful organisation and purposeful tactics for our Party. “The analysis” of this material must, however, be done in dependently, since there are no ready-made models to be found anywhere. On the one hand, the Russian working-class movement exists under conditions that are quite different from those of Western Europe. It would be most dangerous to have any illusions on this score. On the other hand, Russian Social-Democracy differs very substantially from former revolutionary parties in Russia, so that the necessity of learning revolutionary technique and secret organisation from the old Russian masters (we do not in the least hesitate to admit this necessity) does not in any way relieve us of the duty of assessing them critically and elaborating our own organisation independently.

In the presentation of such a task there are two main questions that come to the fore with particular insistence:

1) How is the need for the complete liberty of local Social- Democratic activity to be combined with the need for establishing a single—and, consequently, a centralist—party? Social-Democracy draws its strength from the spontaneous working-class movement that manifests itself differently and at different times in the various industrial centres; the activity of the local Social-Democratic organisations is the basis of all Party activity. If, however, this is to be the activity of isolated “amateurs,” then it cannot, strictly speaking, be called Social-Democratic, since it will not be the organisation and leadership of the class struggle of the proletariat.

2) How can we combine the striving of Social-Democracy to become a revolutionary party that makes the struggle for political liberty its chief purpose with the determined refusal of Social-Democracy to organise political conspiracies, its emphatic refusal to “call the workers to the barricades” (as correctly noted by P. B. Axelrod), or, in general, to impose on the workers this or that “plan” for an attack on the government, which has been thought up by a company of revolutionaries?

RussianSocial-Democracy has every right to believe that it has provided the theoretical solution to these questions; to dwell on this would mean to repeat what has been said in the article, “Our Programme.” It is now a matter of the practical solution to these questions. This is not a solution that can be made by a single person or a single group; it can be provided only by the organised activity of Social- Democracy as a whole. We believe that the most urgent task of the moment consists in undertaking the solution of these questions, for which purpose we must have as our immediate aim the founding of a Party organ that will appear regularly and be closely connected with all the local groups. We believe that all the activity of the Social-Democrats should be directed to this end throughout the whole of the forthcoming period. Without such an organ, local work will remain narrowly “amateurish.” The formation of the Party—if the correct representation of that Party in a certain newspaper is not organised—will to a considerable extent remain bare words. An economic struggle that is not united by a central organ cannot become the class struggle of the entire Russian proletariat. It is impossible to conduct a political struggle if the Party as a whole fails to make statements on all questions of policy and to give direction to the various manifestations of the struggle. The organisation and disciplining of the revolutionary forces and the development of revolutionary technique are impossible without the discussion of all these questions in a central organ, without the collective elaboration of certain forms and rules for the conduct of affairs, without the establishment—through the central organ—of every Party member’s responsibility to the entire Party.

Inspeaking of the necessity to concentrate all Party forces—all literary forces, all organisational abilities, all material resources, etc.—on the foundation and correct conduct of the organ of the whole Party, we do not for a moment think of pushing other forms of activity into the background—e.g., local agitation, demonstrations, boycott, the persecution of spies, the bitter campaigns against individual representatives of the bourgeoisie and the government, protest strikes, etc., etc. On the contrary, we are convinced that all these forms of activity constitute the basis of the Party’s activity, but, without their unification through an organ of the whole Party, these forms of revolutionary struggle lose nine-tenths 01 their significance; they do not lead to the creation of common Party experience, to the creation of Party traditions and continuity. The Party organ, far from competing with such activity, will exercise tremendous influence on its extension, consolidation, and systematisation.

Thenecessity to concentrate all forces on establishing a regularly appearing and regularly delivered organ arises out of the peculiar situation of Russian Social-Democracy as compared with that of Social-Democracy in other European countries and with that of the old Russian revolutionary parties. Apart from newspapers, the workers of Germany, France, etc., have numerous other means for the public manifestation of their activity, for organising the movement— parliamentary activity, election agitation, public meetings, participation in local public bodies (rural and urban), the open conduct of trade unions (professional, guild), etc., etc. In place of all of that, yes, all of that, we must be served—until we have won political liberty—by a revolutionary newspaper, without which no broad organisation of the entire working-class movement is possible. We do not believe in conspiracies, we renounce individual revolutionary ventures to destroy the government; the words of Liebknecht, veteran of German Social-Democracy, serve as the watchword of our activities: “Studieren, propagandieren, organisieren”— Learn, propagandise, organise— and the pivot of this activity can and must be only the organ of the Party.

- Marx and Engels, The Manifesto of the Communist Party (Select ed Works, Vol. I, Moscow, 1958, pp. 42-43). P. 216

ABRE COMILLAS es una columna que recoge citas, transcripciones y fragmentos textuales en donde importantes actores reflexionan en torno a una producción cultural alternativa.