The day is June 25, 1975. The Machava stadium is bursting at the seams and anxiously waiting for this moment. The main character gets on the stage and approaches the microphone, smiling and impressive: Samora Machel.

“On behalf of all Mozambicans, today, June 25, 1975, at midnight, the FRELIMO Central Committee solemnly proclaims the total and complete independence of Mozambique and its constitution in the Popular Republic of Mozambique.”

(Independence speech by Samora Machel, 25/06/1975)

Fighting for Mozambique

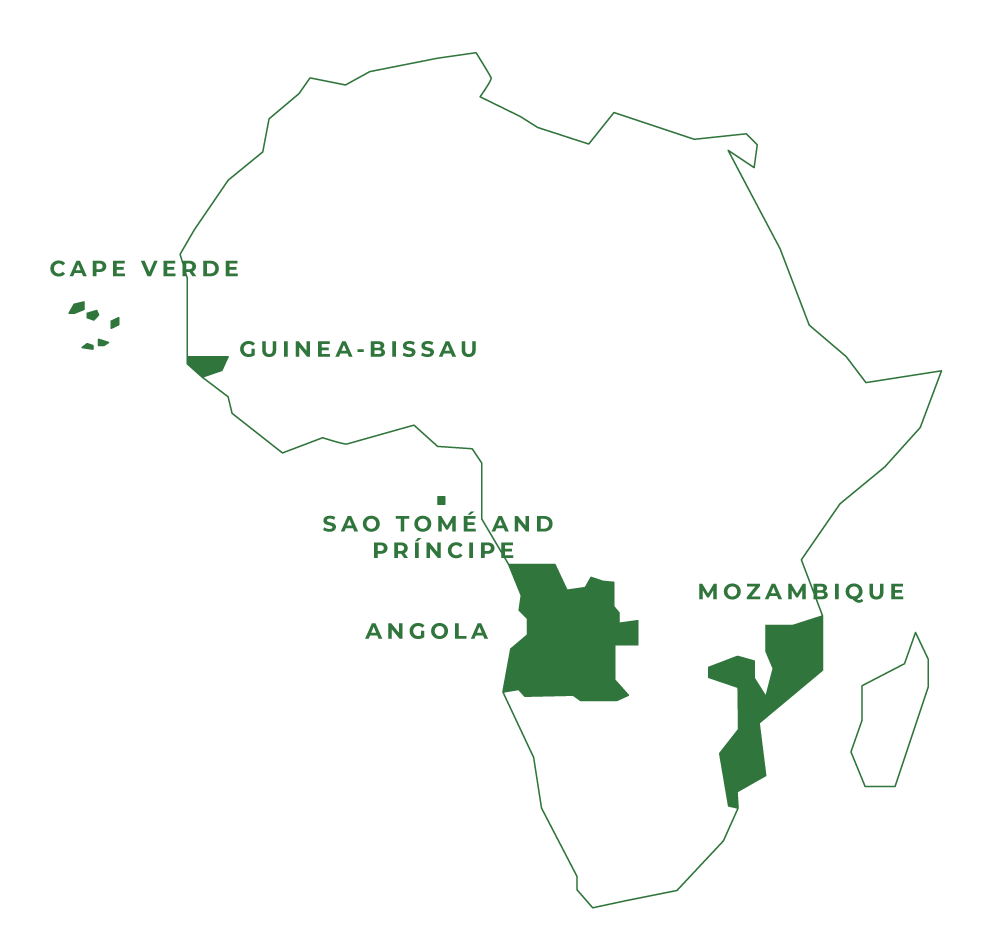

Despite being one of Europe’s most backward countries at the time, Portugal was the last one to grant independence to its African colonies. The contradictions in the colonial model grew ever larger, but Oliveira Salazar’s fascist dictatorship refused to renounce its old “empire”.

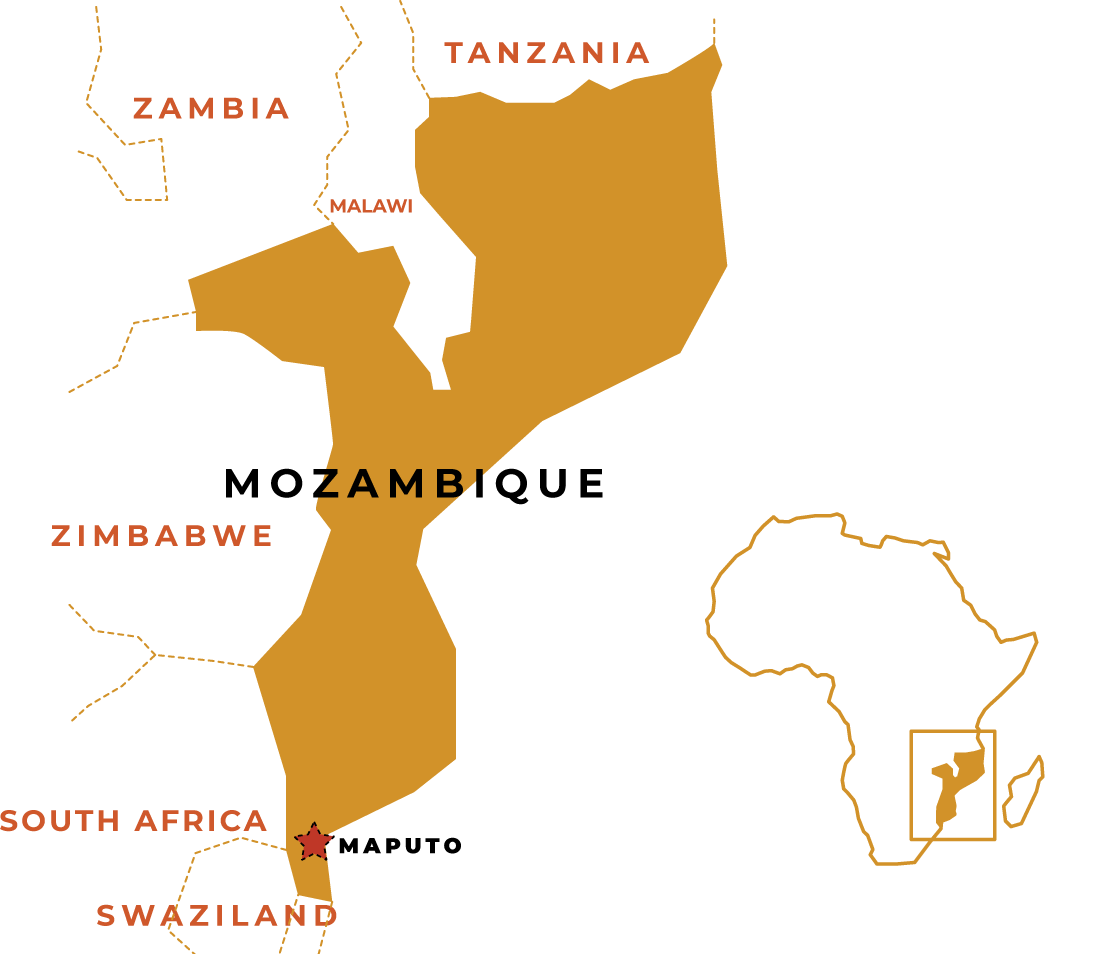

Nevertheless, the winds of independence were already blowing throughout the continent and Mozambique was no exception. Several independent movements were formed, especially in the center and north of the country, with support from Tanzania and Julius Nyerere. On June 25, 1962, these movements unified to form the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO). Two years later, on September 25, 1964, FRELIMO would begin its armed struggle against the colonial regime.

“Today, FRELIMO proclaims the armed insurrection of the Mozambican people against Portuguese colonialism, towards the achievement of the total and complete independence of Mozambique. Our struggle will not cease until the elimination of Portuguese colonialism.”

(Statement by the FRELIMO Central Committee, 25/09/1964)

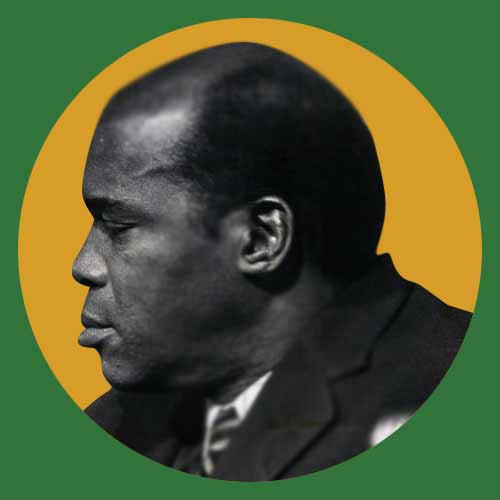

FRELIMO embraced a socialist position from the start, and its first leader was Eduardo Mondlane. Like other leading figures in African liberation movements, such as Guinea-Bissau’s Amílcar Cabral, Mondlane was an intellectual who had studied abroad (in Portugal and the United States). And like in many other cases, Mondlane would also reach the conclusion that Mozambique would not achieve its independence via a negotiated solution with the Portuguese regime.

In 1968, he wrote the manifesto “Fighting for Mozambique” (“Lutar por Moçambique”), but the book would only be published posthumously. Mondlane was assassinated with a bomb concealed in a book by the Portuguese secret police (PIDE) on February 3, 1969.

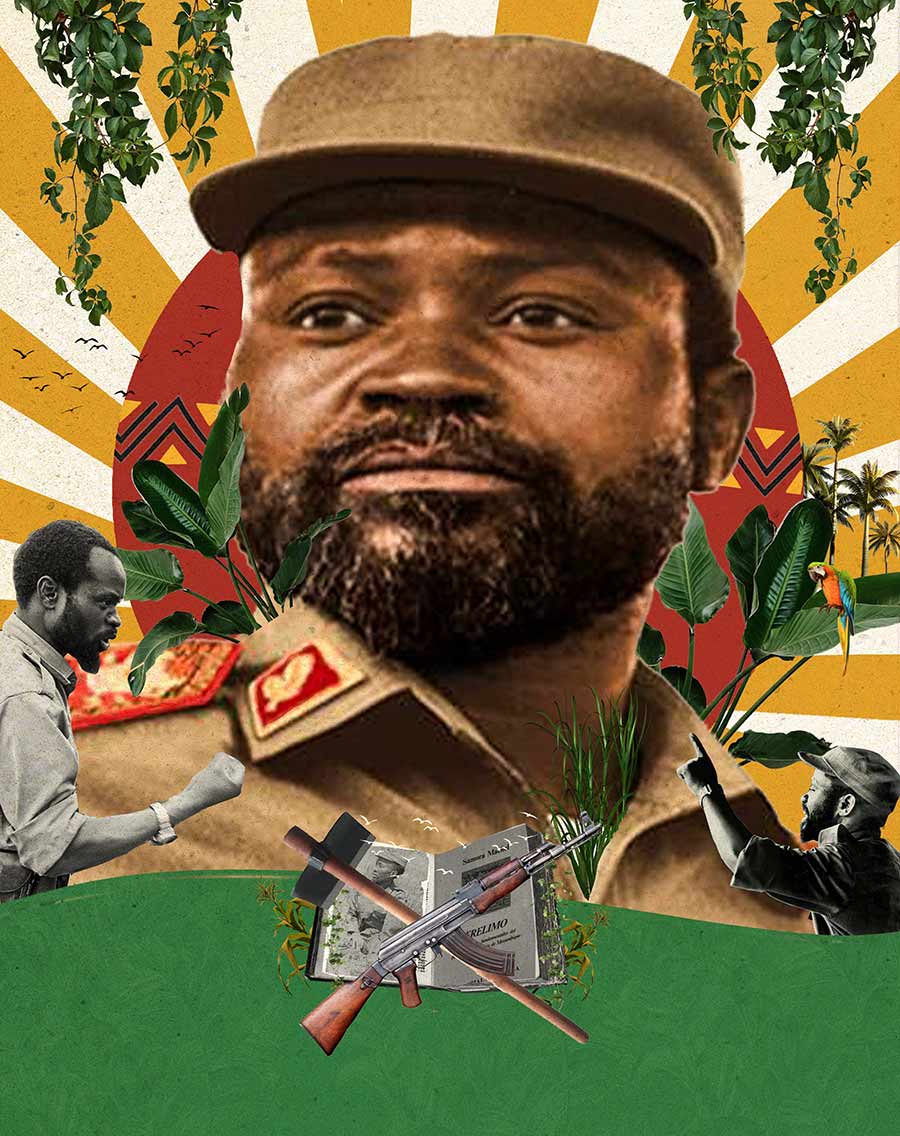

Without its historical founder, FRELIMO turned its hopes to a new leader, the young and charismatic Samora Machel. An inspiring figure who left no one indifferent, Machel is the most important figure in Mozambican history.

By the end of the 1960s, beginning of the 1970s, the Portutguese position in its colonies (essentially Guinea-Bissau, Angola and Mozambique) was becoming more and more untenable. The colonial war demanded ever more human and material resources out of a backward country under a fascist dictatorship. In Mozambique, FRELIMO’s guerrillas kept outmaneuvering the colonial army and extending further towards the south..

Finally, under pressure from the colonial war and domestic clandestine resistance, the Portuguese regime was overthrown by the Carnation Revolution on April 25, 1974. The colonies’ independence was one of the first commitments from the new revolutionary government in Portugal.

Independence or death

To say that FRELIMO was facing an uphill battle following independence would be quite an understatement. Before them stood an extremely underdeveloped country, with a barely existent infrastructure and a tremendous scarcity of (technical and political) cadres. But the party had an unquestionable legitimacy and a firmly set socialist horizon.

The first years of independence were marked by lots of enthusiasm, some mistakes and excesses, and enormous sacrifices as well. High-school students were recruited as school teachers in remote villages. University students were tasked with assuming the leadership of regional administrative bodies. Young graduates were called upon to run state companies.

It was also a time of remarkable solidarity. FRELIMO firmly embraced marxism-leninism after independence, and from the socialist bloc came dozens of technicians, engineers and university professors. Thousands of young Mozambicans were also sent abroad to study, especially to East Germany and Cuba. In Cuba, there was an entire neighborhood of Mozambican students.

The project continued to advance behind a true “locomotive” that was Samora Machel. In his speeches he would always stress that “the struggle continues!” (“a luta continua!”) and was tireless in confronting some of the most reactionary and deeply entrenched elements of society, such as gender inequality and tribalism. And a key factor was that the party led by example. “We should be the last ones to enjoy the benefits and the first ones to make sacrifices,” Machel insisted time and again.

“The offensive now underway is the beginning of a new war. A war against underdevelopment, which will turn Mozambique into a strong country, where Mozambicans will have work, food, quality education and healthcare, dignified housing. It is for these goals that we have always struggled, and it is for them that we endure hardship.”

(Samora Machel speech from 1979)

In spite of the difficulties, FRELIMO did not surrender its plans, and in 1980 launched the so-called Indicative Prospective Plan (PPI). A detailed and ambitious program for the 1980s, it set targets such as the eradication of illiteracy and significant improvements to the population’s living standards. The state was to take the lead with major infrastructure projects and advances in agriculture and industry.

There is no way of knowing whether these goals would have been met, because foreign agents did not allow the country to find out. The specter of war, which hung from the very beginning, landed in full force in the 1980s to halt and destroy Mozambican dreams.

War and neverending underdevelopment

The Popular Republic of Mozambique was born surrounded by enemies. Ian Smith’s racist regime in Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe) stood to the west, and South Africa’s apartheid to the south. For these two countries (and of course for the United States) it was unacceptable to have a nearby socialist country which furthermore stood in solidarity with liberation movements: ZANU in Zimbabwe and the ANC in South Africa.

The strategy was creating and supporting a rebel movement (called RENAMO) which sowed terror and destruction throughout the country. RENAMO never had a chance to win militarily and seize power, but it did manage to paralyze the country. The rebels blew up bridges, schools and healthcare centers, burned factories, killed cadres, committed massacres all over the place, forcing the Mozambican government to dedicate time, effort and resources to fight them.

The final blow to the revolutionary aspirations came on October 19, 1986. When returning from a meeting in Zambia, Samora Machel’s plane crashed in Mbuzini (South Africa). To this day, many hold that the apartheid regime had a hand in this “accident.”

From this point one could fast forward to the present: the inevitable peace negotiations, the inevitable departure from the socialist project, the inevitable arrival of the IMF, the inevitable liberal democracy, the inevitable corruption, the inevitable leadership which grew comfortable in power. In other words, the inevitable and neverending underdevelopment.

The current Mozambican landscape is typical of Africa. Poverty, underdevelopment, foreign dependence, corruption and a host of evils befall a majority condemned to live in misery so as to sustain local elites and especially those in the Global North.

Looking at structural elements, such as the colonial past or the civil war, one could argue that this destiny was somewhat inevitable. But for a few years, alongside Samora Machel, the Mozambican people had the fortune of being able to dream a different future, a better and more just one. The struggle continues!

Research and text: Ricardo Vaz. Artwork: Cacica Honta. Design: Kael Abello.