“I ain’t going to jail no more. The only way we gonna stop them white men from whupping us is to take over. We’ve been saying ‘Freedom’ for six years and we ain’t got nothin’. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power.” (1)

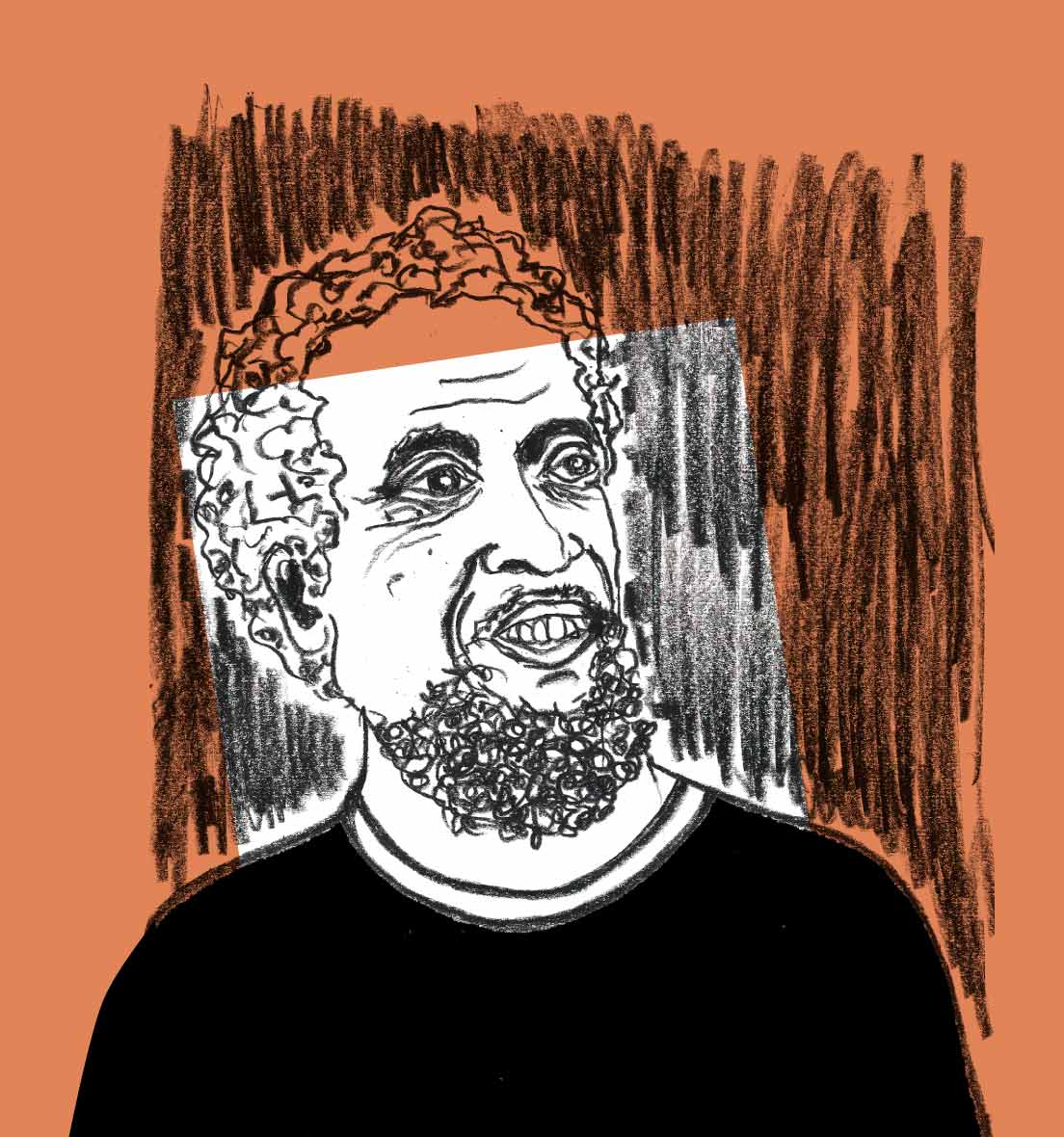

Stokely Carmichael was born on June 27, 1941. Later known as Kwame Ture, Carmichael is one of the outstanding figures of the Black liberation movement in the United States. An equally gifted political organizer and orator, with charisma and wit to sell, he introduced the concept of “Black Power” into public discourse in the late 1960s.

Civil rights and beyond

Born in Trinidad, Stokely joined his parents in the US aged 11, living in Harlem and later the Bronx. He would credit “stepladder speakers,” orators who spoke in Harlem corners about the oppression of African-Americans, as an inspiration for his public speaking skills.

Carmichael began his political activism at 19, taking part in the so-called “Freedom Rides” to challenge segregation in interstate buses and stations. He and other freedom riders were subjected to white mob violence and repeatedly arrested. Stokely was arrested more than 30 times in his life.

After joining the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and graduating from Howard University with a philosophy degree in 1964, the young Carmichael went to the Deep South, the epicenter of the civil rights struggle in the early 1960s.

Alongside grassroots groups and leading figures such as Fanny Lou Hamer, Stokely and SNCC helped organize African-American communities to fight for voting rights in Alabama and Mississippi, while also taking part in the historic Selma to Montgomery March.

However, and despite his star rising in SNCC, Stokely Carmichael would grow disillusioned with the possibility of changing the system from within. Racism was not just a leftover from slavery, it was deeply built into the establishment structures, from state institutions to the Democratic Party. Carmichael also criticized the conciliatory efforts from civil rights leaders, chief among them Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Dr. King’s policy was that non-violence would achieve the gains for black people in the United States. His major assumption was that if you are non-violent, if you suffer, your opponent will be moved to change his heart. He only made one fallacious assumption. In order for non-violence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none.” (2)

Black Power

The 1960s saw the black liberation struggle grow ever more combative. Up and coming leaders such as Malcolm X challenged and called out attempts to sugarcoat the historic and systematic oppression of African-Americans. The Black Panther Party sent shockwaves with their armed demonstration at the California State Capitol.

It was a time of radical speech and action for African-American movements, open talk of socialism and (anti-)imperialism which also coincided with opposition to the Vietnam War. In this context, Stokely Carmichael introduced and popularized a concept just as powerful as polarizing: Black Power.

In his view, there was a need for a break with the civil rights discourse that seemed more interested in keeping the enemy at ease, even more so with the limited gains brought by legislation.

A new generation of voices, including George Jackson, Fred Hampton, Huey Newton, Elaine Brown, Carmichael and several others were adamant that African-Americans needed to struggle for self-determination, not vie to take part in a system built on their oppression. They needed to discard the false paradigm of “integration.”

“Since 1966 the cry of the rebellions has been Black Power. This cry implies an ideology that the masses understand instinctively. It is because we are powerless that we are oppressed—and it is only with power that we can make the decisions governing our lives and our communities. [Black Power] attacks racism and exploitation, the horns of the bull that seek to gore us.” (3)

Black Power was not well received by the more moderate civil rights leaders, King chiefly among them. And it was beyond controversial among white audiences, liberal and conservative alike. Carmichael and others made no effort to allay these fears. As they explained, it was not up to the white people to impose definitions, and it was certainly not up to the oppressed to ensure that their oppressors did not feel threatened.

The role of white activists in the African-American liberation struggle was another recurrent topic of debate, one which actually reappears in lots of other contexts. While in general white allies were welcomed, revolutionary leaders often criticized white activists for searching for a purer/easier struggle rather than questioning their own privilege or tackling the injustices stemming from their own communities.

Africa and Pan-Africanism

The revolutionary effervescence of the Black liberation movement, with tangible advances such as self-defense initiatives or community-run breakfast programs, also made it a central target for US so-called security agencies, particularly the FBI’s COINTELPRO.

In a memo, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover warned of the dangerous possible emergence of a “messiah” who would unify the different African-American organizations. Malcolm X, killed in 1965, would have been a candidate. Hoover dismissed Elijah Muhammad (leader of the Nation of Islam) and Martin Luther King, arguing instead that Stokely Carmichael “had the necessary charisma to be a real threat.”

Repression went to a new level. Fred Hampton was killed in cold blood, while the hammer of (in)justice fell on Panthers like Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton. Constantly harassed and threatened, Stokely Carmichael left the United States in 1969 and established himself in Guinea.

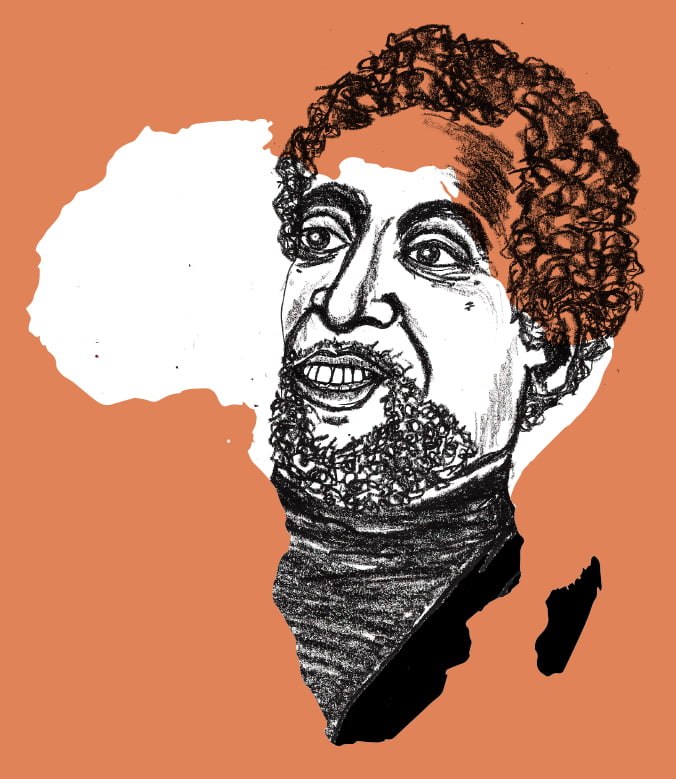

With his revolutionary vision gravitating ever more towards Pan-Africanism, he joined the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party and changed his name to Kwame Ture in honor of the two main early leaders of African independence: Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana) and Ahmed Sékou Touré (Guinea).

For the next three decades, Ture would remain actively involved in intellectual production and political organizing. He frequently toured the US to give lectures and speeches. With firm anti-imperialist convictions, he urged those who listened to see the fight for self-determination in Africa and the United States as part of the same Pan-African struggle and not get caught in a “tribalistic” perspective.

Beyond a simplistic Garveyite recipe of returning to the homeland, Kwame Ture argued that the suffering of Africans in Africa and in the diaspora were two sides of the same coin, consequences of European and later US imperialism.

“On the question of land, the white man divided the African into two groups. One group he took from the land. That’s us: slavery. The second group, he took the land from them. That’s our brothers and sisters on the continent: colonialism. That’s why any African today is a landless man.” (4)

Kwame Ture died of cancer on November 15, 1998, having remained politically and intellectually active until the very end. The global and local contexts saw setbacks for the Black Power and Pan-Africanist causes he fought for, but he never chose the easy road of moderating his views. His unflinching anti-colonialist, anti-imperialist outlook, combined with sharp analysis, made Stokely Carmichael / Kwame Ture a mainstay for future revolutionary movements.

(1) Speech in Greenwood, Mississippi, June 1966

(2) Black Power Mixtape, 1967

(3) First Conference of the Organization of Latin American Solidarity, Cuba, July 1967

(4) From Black Power to Pan-Africanism, California, March 1971

Research and text: Ricardo Vaz. Illustrations: Daniela Castelly. Graphic design: Kael Abello.