ESP – ENG

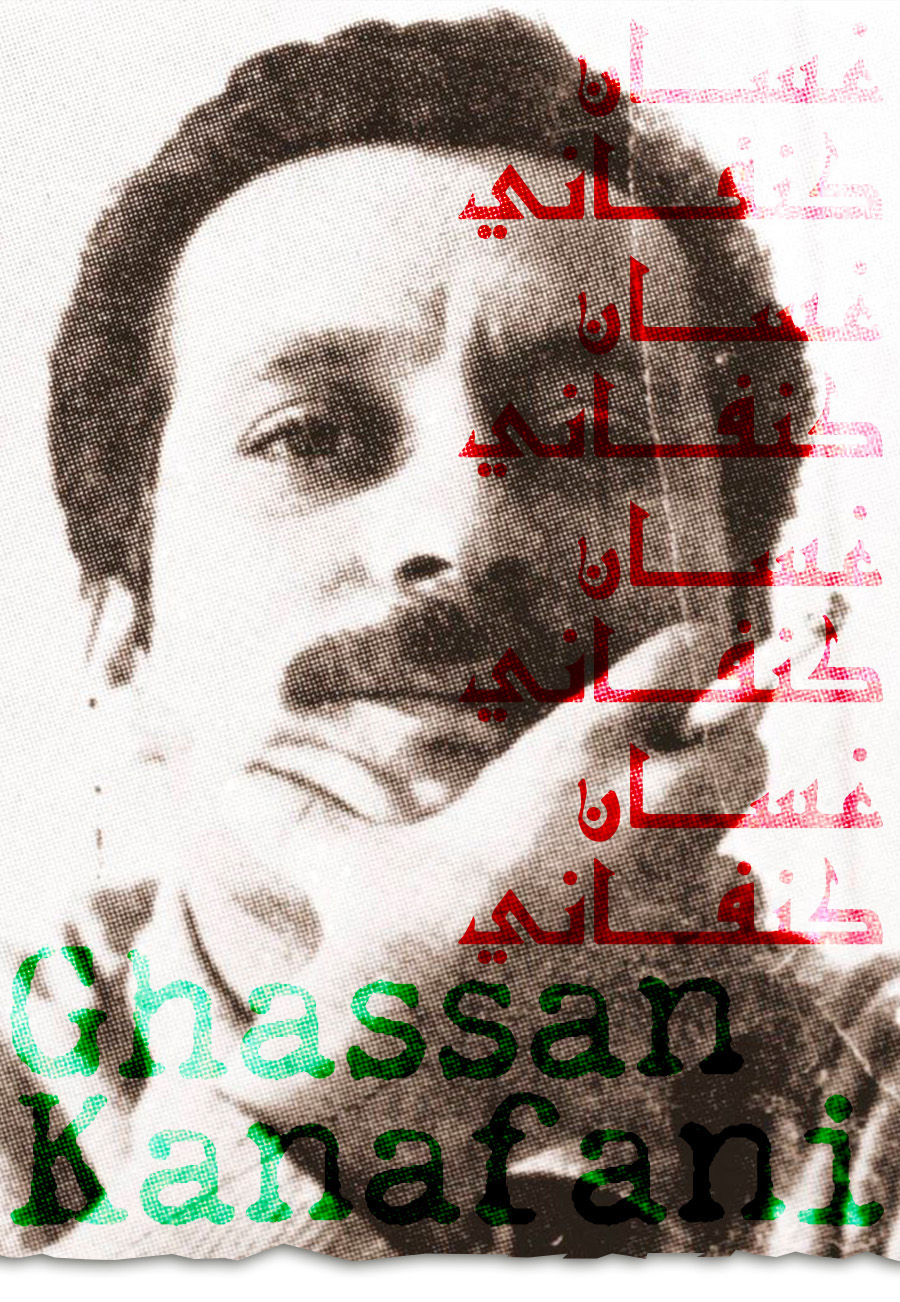

Ghassan Kanafani was a revolutionary writer, journalist and artist, one of the legendary figures of the Palestinian liberation movement. On the 50th anniversary of his assassination by the Mossad, we look back at his life and legacy.

Politically committed novelist

Kanafani was born on April 8, 1936, in Acre, Palestine. He lived in Jaffa until his family was uprooted during the 1948 Nakba. He would eventually settle in Damascus, but not before spending time in refugee camps. Having lived and later taught in UNRWA camps, this would become a recurring feature in his writings.

His political activity began during his Arabic Literature studies at Damascus University. Kanafani met his lifelong comrade George Habash, who led the Movement of Arab Nationalists (MAN). The political activismo got Kanafani expelled from the university. After some time teaching in Kuwait, he moved to Beirut in 1960 on Habash’s invitation to join the editorial team of the MAN newspaper al-Hurriyya (“Freedom”).

Kanafani flourished as a journalist, working in other Arab nationalist publications on the issue of Palestinian liberation. The 1960s also saw the young revolutionary begin to write prolifically.

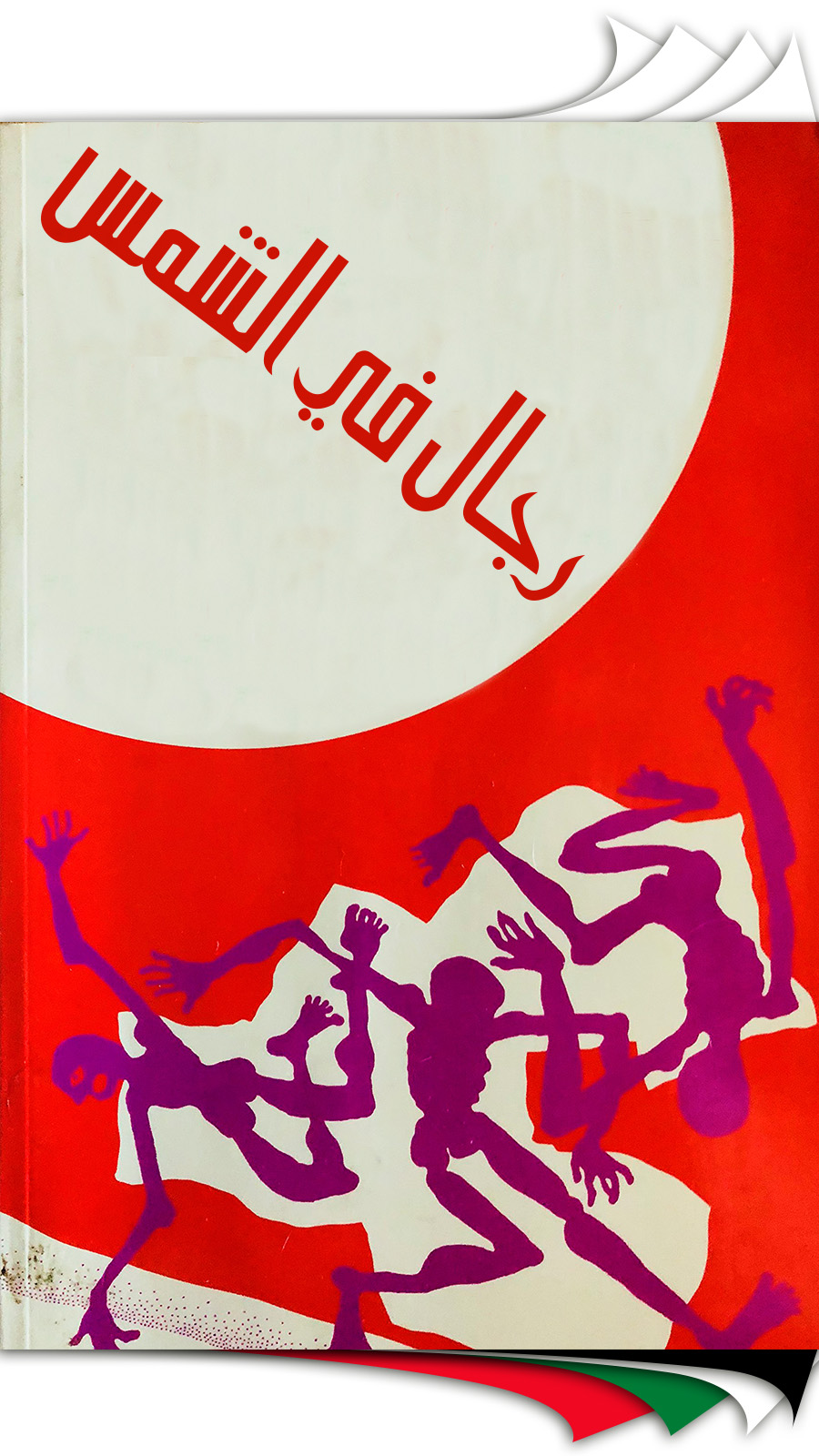

Men in the Sun (1962) is perhaps Kanafani’s most acclaimed literary work. The short novel tells the tale of three Palestinians in exile who die in an empty water tanker while being smuggled as their driver gets delayed at a checkpoint. The deaths are not blamed on the blazing heat but on the victims’ silence as they suffer. One characteristic across Kanafani’s writings is his depiction of ordinary Palestinians. Neither cartoonish heroes nor martyrs, they are ordinary people, driven by noble or petty motives. But the background is always the crude and tragic reality the Palestinian people face, be it in exile, under occupation or in refugee camps.

Kanafani was always adamant that his politics and his writing were not separate endeavors. “I became politically committed because I am a novelist, not the opposite,” he once said. He coined the term “resistance literature” and claimed Palestinian authors “write for Palestine with blood” in reference to the inability to escape their roots of occupation and dispossession.

From Arab nationalism to the PFLP

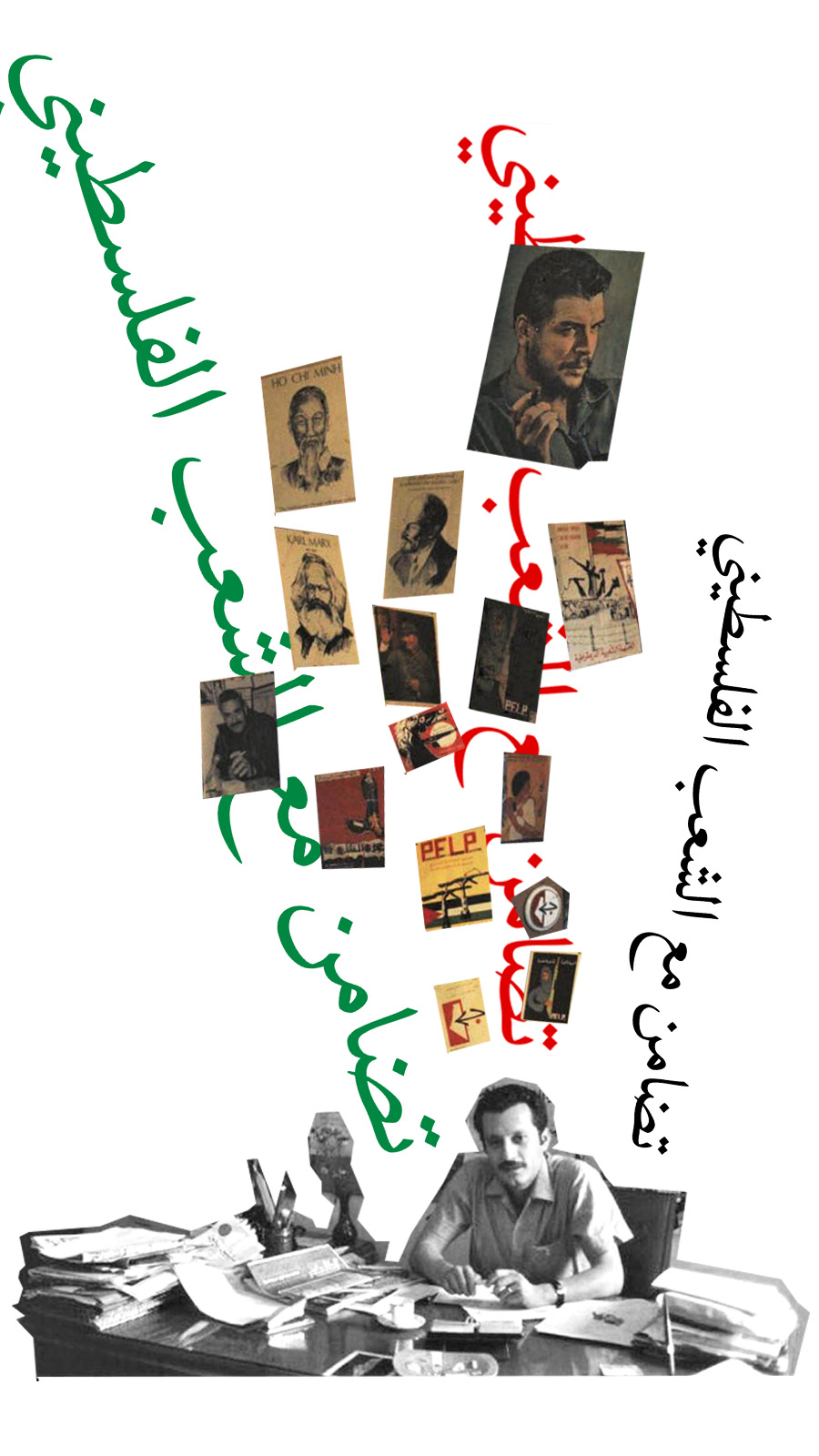

The Nasser-led Arab nationalism suffered a fatal blow with the defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War. Habash, Kanafani and others finished their transition to Marxism-Leninism and founded the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

The late 1960s were a period of radicalization for the Palestinian liberation struggle, now organized under the PLO umbrella, where the PFLP was the second-largest faction behind Yasser Arafat’s Fatah.

The most revolutionary factions understood and portrayed the Palestinian struggle within a global anti-imperialist fight. “Our enemy in the battle is Israel, Zionism, world imperialism and Arab reaction,” read the PFLP’s 1969 Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine, drafted by Kanafani and others.

As such, Palestinians needed to take charge of their own destinies and not be held hostage to reactionary Arab regimes who used, and continue to do so, Palestine to further their own interests. It was always a contradiction for Palestinian liberation to hinge on medieval throwbacks like the Hashemites or the Saud family whose very existence is a consequence of imperialism.

Armed struggle and the fidayeen would become recurring themes in Kanafani’s short stories, but without glorifying a path that was very much of sacrifice for a young generation.

One of his major novellas written during this time was Return to Haifa. Narrating different timelines that are beautifully woven together, Kanafani tells the (fictional) tale of a Palestinian couple that returns to their former home to find it occupied by a Polish Jewish family that survived the Holocaust. Not just that, they adopted and raised the Palestinian couple’s baby, who was left behind when Palestinians were forced to leave Haifa in 1948. The story leads the Palestinian protagonists (and Kanafani himself) to conclude that only armed struggle will liberate their homeland. It is also interesting because it depicts the human side of the Jewish occupiers, even if they are the manifestation of a ruthless colonial project. It is a humanity that has always been hard to find in Israel’s reign of violence, evictions and terror. And certainly a humanity that the occupier has never granted to Palestinians.

As essential as life itself

Kanafani was a key figure in the PFLP, serving as a spokesman and leading its official organ al-Hadaf (he was posthumously made a member of the politburo). Unbeknownst to many, he was also an accomplished artist who designed several iconic posters that would become some of the most recognizable imagery of the fight to free Palestine.

Palestinian liberation was, in his words, “a cause for every revolutionary,” and his efforts in different fields were massive in internationalizing the struggle in the Arab world and beyond.

Kanafani left a massive trove of stories, essays, art and a lot more. Thanks to the efforts of his wife, Annie Kanafani (née Hoover), and political comrades, much has been made available in other languages. In one interview excerpt, released not so long ago, the PFLP cadre remarkably tore apart misconceptions and made clear what an emancipation struggle is all about.

Australian journalist Richard Carleton saw his misleading, if well-meaning, questions about the possibility of “talking” to the Israelis dismissed eloquently as “a conversation between the sword and the neck.” As Kanafani argued, it is not for liberation movements to talk to colonists, and the Oslo Accords would tragically reinforce this point. After all, the zionist occupation of Palestine is not a misunderstanding.

But perhaps the most remarkable point Kanafani makes is rejecting the idea that somehow it would be worth it to stop fighting so no one else would die.

“To us [Palestinians], to liberate our country, to have dignity, to have respect, to have our mere human rights, is something as essential as life itself.”

The commando who never fired a gun

It is no mystery why Kanafani was pinpointed by the Israeli occupation and its foreign sponsors as someone to eliminate. Charismatic and prolific, combining art, literature and journalism, he was key for Palestinian advances in the battleground of public opinion.

The PFLP revolutionary was killed, alongside his 17-year-old niece Lamis, by a Mossad car bomb on July 8, 1972, as he left his home in Beirut. He was only 36 years old. “A commando who never fired a gun,” his obituary read.

Zionists thought that killing Kanafani would make him disappear. But alas, like many other oppressors who thought likewise found out, it was not to be the case. From murals to social media profile pictures to newly edited books, Ghassan Kanafani is as popular as ever as a political, artistic and literary inspiration for new generations.

Collaborationists and conciliators might get feted by the occupiers, they might enjoy opulent lifestyles as they hurt the cause they once stood for. They might even win Nobel Peace Prizes. But in spite of massive media campaigns, the people do not forget who their heroes are. It is Kanafani and others like him who continue to inspire struggles for a better world and especially for the liberation of Palestine. They are the ones who embodied collective causes and fought for them until their last breath. And that is as essential as life itself.

Research and text: Ricardo Vaz. Artwork: Luis Cario.