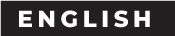

March 5 marks the 150th anniversary of Rosa Luxemburg, a key figure for the revolutionary left in early XX century Europe. A tenacious militant, she was killed in 1919 and left a legacy that would later be claimed by communists and the reformist left alike. The numerous letters she wrote from prison also turned her into a revolutionary romanticism icon, thus softening the edges of a life full of battles. Among these, her opposition to World War I (1914-18) is crucial to understand why her thought remains as relevant as ever.

In this sense, we must consider the magnitude of the cataclysm produced by the approval of war credits by a host of social democratic parties in August 1914. Grouped since 1889 in the Workers’ International, these parties had opposed war and imperialism for years, arguing that it was all a matter of rivalries between national bourgeoisies in which the workers should not get involved under any circumstances. Nevertheless, with the conflict on their doorstep, most of them melted into the “sacred union” on a national level and sided with their respective bourgeoisies. The German Social Democratic Party (SPD), the largest working class party in the world at the time and the biggest in Germany in terms of members and Reichstag deputies, also betrayed decades of internationalist commitment.

An SPD member since the late XIX century, Rosa Luxemburg had made no effort to conceal her contempt for some of the party leaders after they abandoned any and all revolutionary pretenses. The issue was that the SPD, given its size, in the decade of 1910 became a sort of parallel society that sustained hundreds of permanent members, journalists, intellectuals, etc… This complex organization became its strength and a model for many revolutionaries around the world, but it also dampened its radical outlook insofar as many of its leaders became comfortable with the status quo. Rosa Luxemburg thus found herself in a disadvantageous position inside the party, especially after alienating most of its high-ranking figures, Bebel and Kautsky among them.

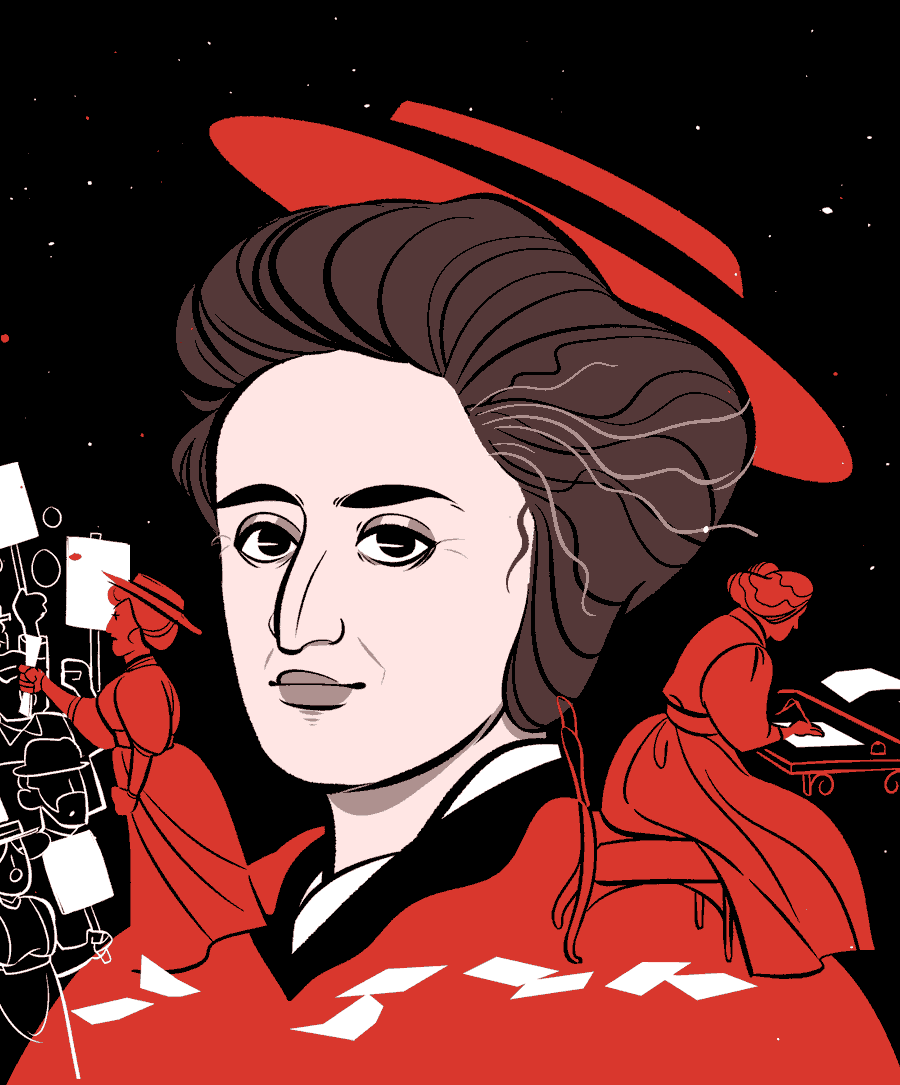

The August 4, 1914 betrayal, when the Reichstag unanimously approved war credits, did not come as total surprise for her. A longtime opponent of war and militarism, she was jailed in February 1914 for a speech in which she called on soldiers to disobey their superiors. Luxemburg spent most of the war in prison, and from her cell she tried to organize the dissenting voices which grew ever more numerous inside the SPD as the war ground to a halt. The party’s leftist elements were soon forming underground organizations, since a pacifist position during the war was against the law. These groups soon became known as the “Spartacus League,” and this name was signed on most of their anonymous publications. The league would become the core of the German Communist Party a few years later.

Nevertheless, Rosa Luxemburg and her allies remained loyal to the SPD until a very advanced stage of the war. This can be understood by the importance the party attributed to mass struggle, both in word and deed. It was better to struggle inside what was the working class party par excellence, even if its leadership was rotten to the core, because this was the only way to reach the masses. And the masses are the ultimate agents of change. As Luxemburg put it: “The discarding of membership cards as an illusion of liberation is nothing but the illusion, stood on its head, that power is inherent in a membership card.”

Through her uncompromisingly internationalist actions, Rosa Luxemburg helped inject a new dynamic into the workers’ movement at the time. She did so alongside comrades who, in every country, had a clear understanding of who benefitted from the slaughter of millions of young people on the battlefields. Her comrade in arms Karl Liebknhecht, murdered on the same day as Luxemburg, struck the same chord when he said that, in every case, the main enemy was inside one’s own country. For his part, Lenin, with whom Rosa Luxemburg had a lively but always respectful correspondence, managed to take the opportunity to “transform the imperialist war into a civil war.”

Nowadays, the international peace movement is but a shadow of what it once was, following its failure to put a stop to a host of military interventions and other proxy imperialist wars. Humanitarian disasters are widespread and people cheer on. Rosa Luxemburg’s 150th anniversary should be an opportunity to regroup and reflect on the bases of a new internationalist peace movement. After all, back in 1914 the war was sold to German socialists as a democratic intervention against the tsar’s autocratic regime. Luxemburg and her people were much less foolish…

L’Atelier – Histoire en mouvement (Atelier-History in motion) is an organization fighting to safeguard and spread the memory of working class, women and oppressed peoples’ liberation struggles. The Atelier’s creation stems from the will to develop a different focus with respect to the one offered by the dominant historiography, so that the rebellions of the oppressed of yesteryear live on in the rebellions today, and so that the path carved by these struggles can pave the way for tomorrow’s emancipation.

Artwork: Metmarfil. Translation: Ricardo Vaz