ESP – ENG

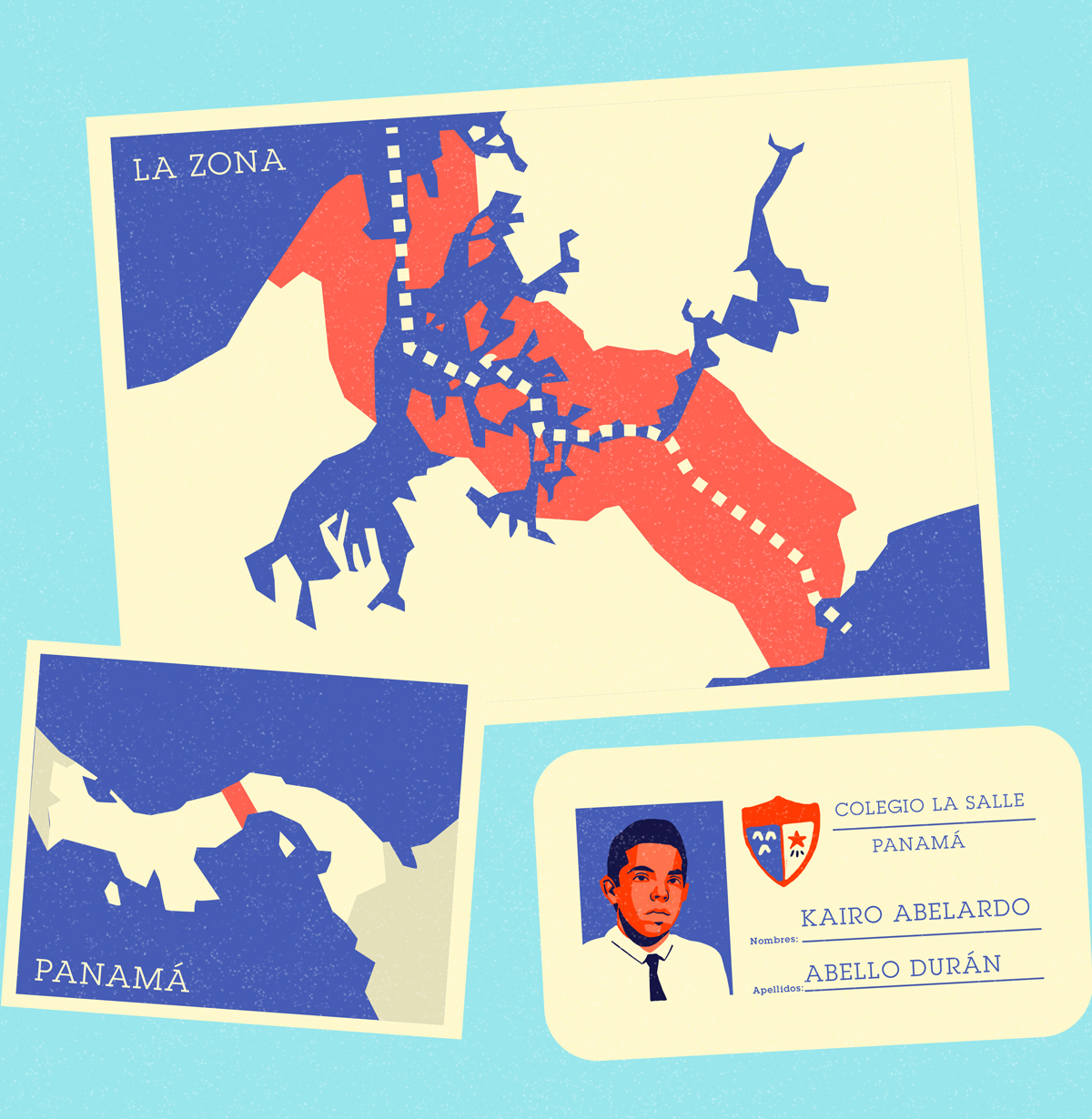

Panama’s recent history has been marked by the United States’ outsized influence, starting from its control of the Panama Canal and surrounding area. A growing patriotic sentiment started to question the US presence more and more. On January 9, Panamanian students tried to hoist the national flag in the US-administered territory and the repression left dozens dead. Kairo Abello, only 15 at the time, recalls his role in the massive protests that took place in the “Martyrs’ Day” that would change the history of Panama.

Sixty years ago I lived through one of Panama’s most transcendental historical episodes. I attended La Salle High School, I was just fifteen years old and getting ready for final exams after the holiday break. I used to study, along with my classmates, in a library in the capital known as the USIS (sponsored by the US). It wasn’t close to my house but it had air conditioning. It was never crowded and had a record collection that we could listen to with headphones (a novelty at the time) which justified making the trip. Furthermore, I think we also wanted to take advantage of what the gringos provided to get a leg up. Being anti-US was very much a part of Panamanian nature. I don’t remember anyone who felt differently, even at the private and religious school I attended.

I was a member of the La Salle student union, something harmless and tolerated by the school. Our vision for social justice went as far as Christian Democracy and the principal saw the student collective as nothing more than a platform to recruit people for organizations like Opus Dei. In contrast, the student movement on a national scale was much more radical, organized and active. The US presence alongside Cuban and Soviet Union influences made for an explosive cocktail amidst the Cold War, with all sorts of protests breaking out regularly, even if they were symbolic for the most part.

I can’t recall how on that January 9th we heard about the assassination of several Instituto Nacional students as they tried to hoist the Panamanian flag inside the US-controlled territory that was simply known as La Zona. The library where we used to study was a couple of kilometers away from the National Assembly and the Instituto Nacional. Both buildings were separated from La Zona by the 4th of July Avenue, in honor of US independence (later renamed as Martyrs’ Avenue). This was usually where protests took place. Therefore, as soon as we heard the news, we headed that way. During the trip, I could see a lot of outraged people spontaneously walking in the same direction.

When we got to the area next to the National Assembly there was already a huge crowd gathered. There was unrest, shouts, ambulances, tear gas smoke and some Molotov cocktails. In the rear there was a National Police patrol just standing by. Among the people there was no politician or deputy I could recognize. I got through until I reached the front. On one side of the avenue people threw stones. On the other, stood the US soldiers with their guns ready behind a barricade.

Once we regrouped we realized that stones would not do anything, so we decided to come back later with some Molotov bombs. There was no public transportation, so it took as a while to get back home. I can’t tell what time it was, but there was still daylight when we finally made it. We gathered bottles, especially small ones so we could throw them farther.

I lived with my grandparents (my parents had moved to Venezuela) and they were very unnerved by what they were hearing on the radio. To get out of the house again I told them we were going to put out a statement from the Student Union. But in truth we got together to set up a couple of dozen Molotovs. Then we walked around looking for some place to test how effective they were. We had brought more bottles than we could load, so I located a gutter to store them alongside a gallon of fuel. Finally, we found a car and headed back to 4th of July Avenue.

It was already dark once we got back to the National Assembly. We left the car far from the crowd and continued on foot. Along the way, a police officer took a Molotov bag from one of my companions. The police were trying to prevent an escalation of violence. But people wanted them to fire on the gringos.

At some point a National Guard patrol arrived at the area and an officer standing on the car door, in a symbolic yet desperate act, fired his gun in the air. The echo from the gunshots was followed by a roar from the crowd that demanded a more active role from the National Guard against the US soldiers. It was not confirmed at the time, but piecing together different stories later on, that officer might have been Omar Torrijos.

We took turns in pairs to get closer to a little fence that separated the National Assembly courtyard from the avenue. That was the Molotov launch point. I saw how they fell halfway from their target and the flames went out in a couple of minutes. On the other side of the road, the US soldiers would occasionally fire their guns. I vividly recall seeing a wave of gunfire in front of me and right afterwards, two meters away, a young men fell with his back bloodied. He was carried towards the ambulances.

This was a reality check, and common sense told me that there was not much we could do in those conditions. We decided to retreat and take stock of the situation. On the way back we went past the library where we had been studying that same morning. An angry crowd threw stones at it. I joined that collective rage and destroying the library became a message: our patriotic pride was not to be bought with some benefits, mirrors and colored beads.

Like all US structures, the library was very well built. It was practically a fortress, designed to prevent all sorts of vandalic efforts. It was shielded by a fence and the windows had metal covers. However, the upper-floor windows were not as safe. I thought that by scaling the fence I could reach the eaves and throw a Molotov cocktail inside. I managed to climb and as I stood on the eave the shattered glass cut my arm. I wasn’t going to be deterred. In contrast, the stones continued to rain and I became a target, so I had no option but to get back down. The next day there was a photo on the papers showing the burnt library. I know it might look like an act of savagery, the work of a vengeful mob. For me, at that time and place, it had a certain meaning.

The days that followed were a political firestorm: news, statements, rumors, out-of-control rallies, funerals, mourning, collective grief and a suspension of school activities. My school decided to do away with final exams and just use students’ average grades. I was just handed a diploma, with no graduation ceremony and no celebration of any kind.

The strange symbiosis between Panama and the US was very intense. There was the military presence, culture, currency, politics, trade, food, fashion, music… It was natural for a certain middle-class to study in the US. A few weeks later, alongside some classmates, I traveled to the US for university studies. The patriotic fire turned into letters and later into memories. In the US, the Vietnam War and the civil rights struggle broadened my anti-imperialist worldview. By then my parents had settled in Venezuela and I never went back to Panama.

Those acts of rage and desperation, futile on the surface, directed against soldiers from the largest global superpower, as well as the assassination of young students, did have consequences. Four years later Torrijos won the presidency and negotiated a new treaty with the US. Then came Noriega, the invasion, the economic boom, the same politicians (the ones who were nowhere to be found during the tragic events of 1964) and a new subservient ruling class that inherited the canal, freed Posada Carriles and built a monument to those who gave their lives on that January 9th.

Nowadays I feel like a tourist when I visit Panama. These distant memories are all I carry.

Flashbacks is a Utopix project that reconstructs testimonies from people who were not necessarily protagonists but witnessed events amidst major historical transformations. The tales take us back to different times and places, but they all offer a view from below and up close of episodes of struggle that forged history.

Text: Kairo Abello. Artwork: Kael Abello.