The Carnation Revolution (April 25, 1974) was the final episode of a long struggle against the fascist dictatorship in Portugal. Eduardo Rother, a fisherman, journalist and internationalist activist, was in Lisbon during this time when «everything seemd possible» and, almost unwittingly, witness a revolt that characterized these agitated and inspiring times in Portuguese history.

A month and a half after the April 25 revolution, a group of us walked through the jubilant Lisbon up the Castle hillside, with the plan of then going down the stairs and alleyways of the old Moorish neighborhood of Alfama to get lost among the crowd that celebrated, with sardines, wine and music, the first “Popular Saints” since the fall of fascism.

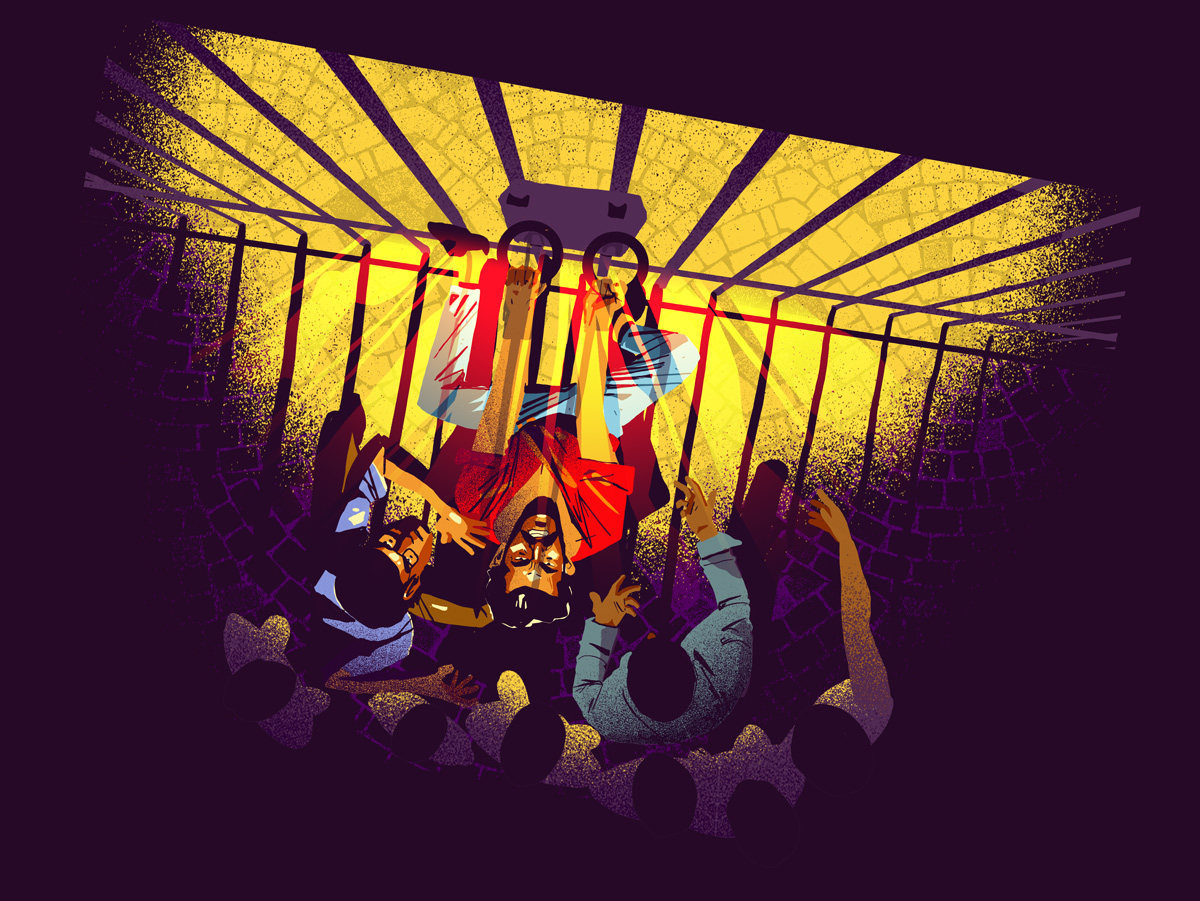

As we walked past the old and harrowing Limoeiro prison, the sound of broken glass on the second floor caught our attention. A few arms stretched out, like worms, out of the windows. There were shouts and metal objects banged against the bars: the common prisoners were restless, but the mutiny was timid and hopeless. At that time in the evening, the few passersby and vehicles paid no attention. We stopped to find out more and our presence encouraged two or three inmates whose figures we could identify in the upper floors. My friend Yoca, with his massive stevedore body and an even bigger heart, shouted out “what’s going on?”.

The clearly useless question made the shouts rise up and plenty of other shadows approached the windows. At the time, a watchman in the sentry overlooking the main metallic gate, loaded up his assault rifle. The sound of a G-3 made my blood freeze: 40 meters away, below on the sidewalk, we were the perfect target.

Yoca, furious, charged toward the guard while hurling provocative screams:

—Fascist, son-of-a-bitch, murderer, bastard! Shoot me! Kill me, you son-of-a-bitch!

The watchman was taken aback, we all were. Yoca tore open his shirt and showed his chest:

—Right here! Shoot right here, coward, bastard murderer!

In normal circumstances, Yoca would have been killed on the spot. But amidst a revolution, two months after the fall of fascism, the police and the National Guard had lost their arrogance and tried to fly under the radar. As if they got a signal, the watchman and all the others standing guard stepped back from their posts. By then, all the windows were brimming with inmates watching the scene.

Yoca, possessed by a previously unknown rage, ran toward the main gate, grabbed the knockers and started banging, generating a hellish noise. Pinho Monteiro smacked me in the arm:

—What are we waiting for? Let’s go!

I was scared, but leaving Yoca all alone would be unforgivable. The whole group ran to help him. The girls screamed for the guards to open up and kicked the gate, which did not open but was promisingly rattled. Dozens of men, throughout the different floors, joined our effort with shouts that were heard in the neighborhood and beyond. The social prisoners, unfittingly called “common,” were no longer alone. The revolution and the people had remembered them, the Limoeiro revolt was underway.

People started to join the scene. With the street at our mercy, buoyed by that popular enthusiasm that made everything possible, we started to engage with the prisoners, shouting questions at them while they sent written notes in plastic bottles or rags with scribbled messages. Our comrade, Fan Casanova, a young army soldier, climbed atop a car and started to read the message out loud as the crowd gathered:

—We are the true victims of fascism. We are here for stealing a lighter, or for other things caused by the misery and ignorance that fascism imposed on us. Why should we remain under the fascist punishment? Is there no democracy and freedom for us? The political prisoners are out and we remain in these dungeons. Why is that?

More people gathered, a few foreigners asked in their own languages what was going on, the trams slowed down. SInce it was the “Popular Saints” party, a giant traffic jam ensued, the largest one in many years. As time went by, Lisbon realized what was going on and came to see. Only the trams managed, with difficulty, to pass through the crowd, and some cars tagged along.

Pinho Monteiro said we needed to stop a tram to block all traffic. We came across one of those old, iconic yellow devices, Afonso climbed on and talked to the passengers.

—Ladies and gentlemen, comrades, the common prisoners want their freedom and demand it from the revolution. It is necessary that the whole people, alongside soldiers and sailors, grant these men a new way of life. We must get them out of these disgusting, medieval prison. There is no authority above us here. We have decided to stop traffic to draw attention. We await the arrival of the soldiers. We want nothing with the police or the guard. This tram cannot move forward, we will not allow it.

Most of the passengers agreed and smiled. After half a century of silence and order, all news was welcome. It was one of those “festivals of truth where no one remains sober.”

A South American, always handy in those situations, unhooked the wire that connected to the electrical system and the tram lights promptly went off.

Soon enough there were a thousand people gathered, of which some two hundred stood still, their gaze fixed on the barred windows. They were relatives of the prisoners who lived in the area. Some dramatic conversations and some cheerful ones too. A beautiful young woman was shouting at her partner after she spotted him on the second floor:

—Antonio, what are you doing this weekend?

—I’m going to the beach. You’re welcome to come too. Buy me a swimsuit.

Finally, after a lot of horn-blaring and sweet-talking, two Military Police vans managed to go through. In the crowd, apart from Fan, there were plenty of military officers and soldiers, some in uniform and others in plain clothes, so the discussion was quick. After a while they announced to the prisoners and the people around: the Armed Forces Movement, and they as the military authority on site, took note of what the prisoners and the people demanded. They, as officers and individuals, supported the idea of freeing all the prisoners, and proposed the immediate set up of a committee with the relatives to organize the liberation process.

When we saw that everything was on the right track, we left the jubilant crowd that sang “Grândola Vila Morena” and went back to the original plan of going to the Alfama festivities. Down stairways and alleys we went, stopping by several stalls to eat roasted sardines with bread and wine, commenting on the outcome of the revolt, which was greeted with sincere joy from those around us. No one expressed any fear about releasing the “commons.” The revolution made everyone feel free, and those who are free fear nothing.

The next day the prisoners were moved to a military installation and a week later they were released. Many joined the army, albeit temporarily. The others went back to their families. There was one who could not believe the miracle, tried to escape during the trip and was shot. Portuguese soldiers were returning from the colonial war and had a quick trigger.

We finished the downhill trip through Alfama, reached a plaza on the river bank and went into a bar on the docks to drink something stronger. The revolt was the conversation subject.

—I was in Limoeiro for a year and it’s very ugly. The worst of Portugal. Back then I was young and a little crazy…

—Oh, so you no longer are?

Once the laughter subsided, an old man who was sitting alone in a small table spoke:

—Limoeiro is very bad, there are some 300 years of suffering there, and it is welcome news if it gets shut down. But it’s not the worst prison in Portugal. In Ponta Delgada in the Azores there is another one, also called Limoeiro, where prisoners have no electricity or running water. As you know, friends, sometimes it can’t get any better for the rich, but for us the poor there is always a way for things to get worse… Always!

Flashbacks is a Utopix project that reconstructs testimonies from people who were not necessarily protagonists but witnessed events amidst major historical transformations. The tales take us back to different times and places, but they all offer a view from below and up close of episodes of struggle that forged history.

Text: Eduardo Rothe. Artwork: Kael Abello. Translation: Ricardo Vaz.