César Nereo Rengifo Cadenas was a painter, essayist, playwright and several other things. On the 40th anniversary of his death, we recall the life and work of one of Venezuela’s most multi-talented intellectuals of the XX century.

Born in Caracas in 1915, Rengifo lost both his parents at a very early age and was raised by José del Carmen Toledo, a close family friend. He would become a strong influence in young César’s precocious development. At just 15 years of age, he entered the Caracas Fine Arts Academy to study drawing, painting and sculpture.

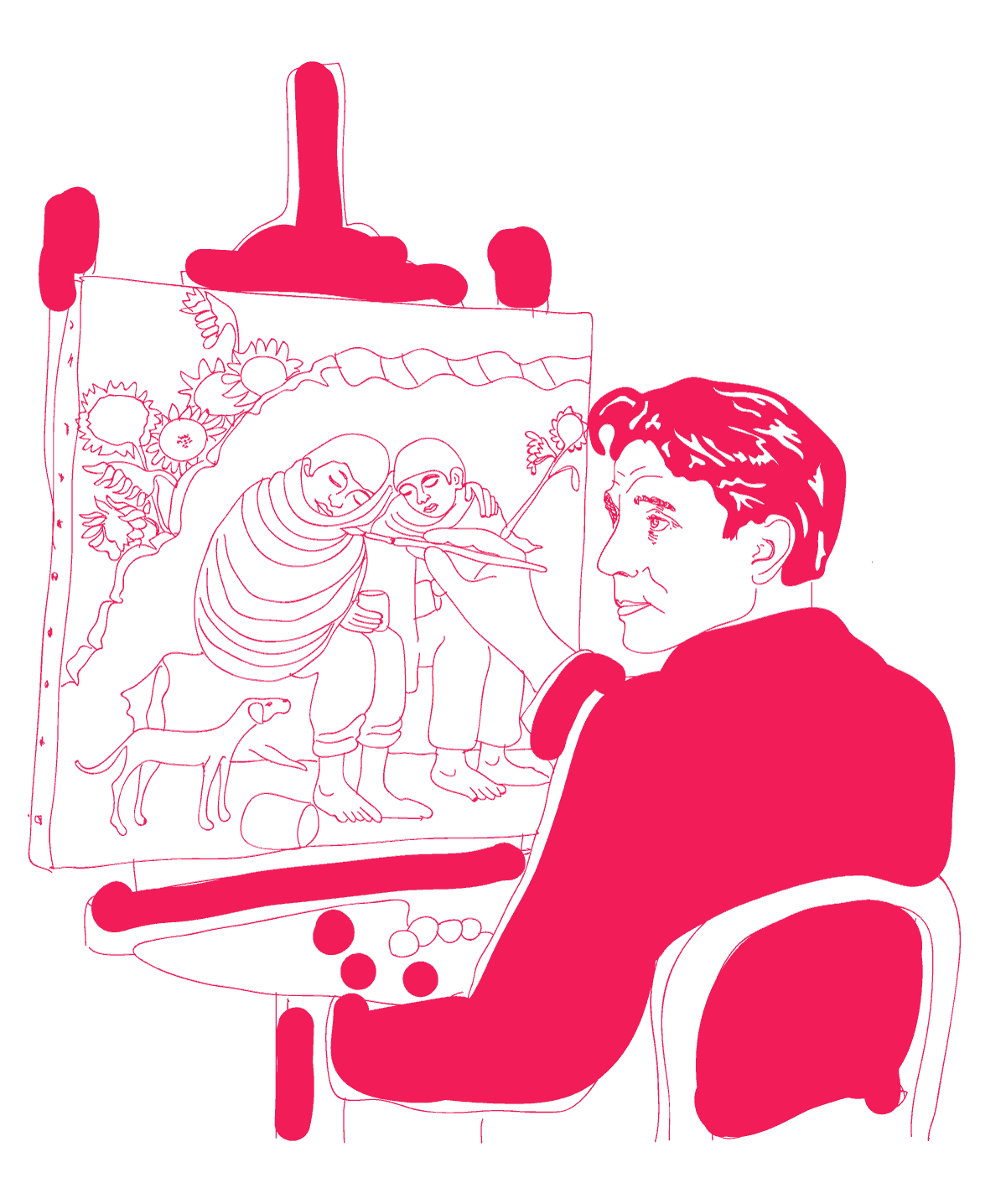

After graduating, Rengifo had the chance to travel to Chile and Mexico, where he met some artists that would come to influence his work, Diego Rivera among them. He returned to Caracas in 1938 and started a renowned and prolific career which included essays, journalism, visual arts and literature. Rengifo held positions in several schools and institutes, and founded the Mérida School of Visual Arts.

César Rengifo was also a man of firm political beliefs who was close to the Venezuelan Communist Party throughout all his life. And those communist ideals are reflected in his work, which always looked to reflect the social struggles of the Venezuelan people.

Rengifo was constantly plagued by health issues, and died in Caracas on November 2, 1980.

Social realism

César Rengifo’s painting is characterized by his attempts to depict Venezuelan day-to-day life, the people’s hopes and frustrations.

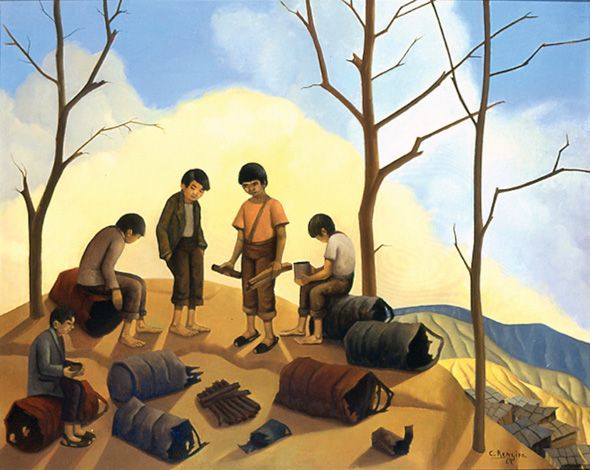

The characters in the paintings often have their backs turned towards the viewer, as if inviting him to witness their reality. Rengifo painted a host of themes, but time and again came back to the phenomenon that changed Venezuela in the first half of the century: the discovery of oil.

Just as he would do in his essays and theater plays, the artist had his paintings reflect the consequences of oil drilling in the Venezuelan countryside. Empty oil barrels, undernourished dogs, desolate scenes laid bare the less glamorous face of the oil boom.

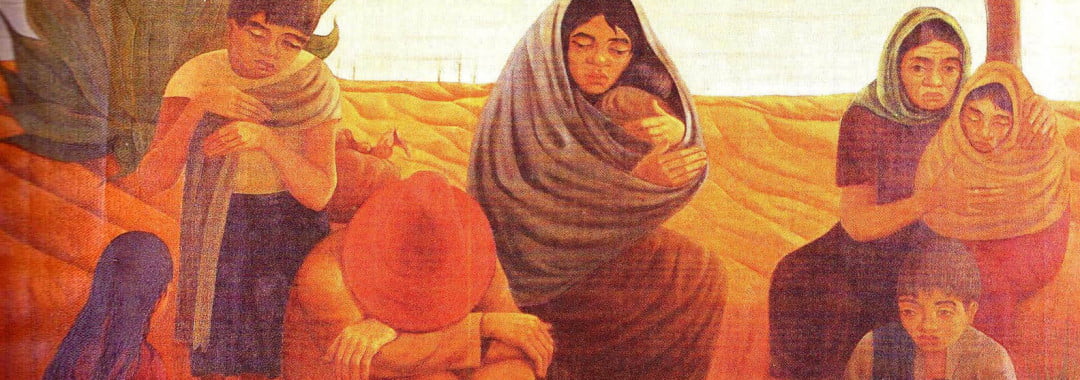

In the same vein, there are several Rengifo paintings showing the rural migration that took place in Venezuela. Driven away by oil operations, or unable to survive amidst the latifundio (large, private, generally unproductive estates), campesino families were uprooted from their land and forced to fight for survival in the cities.

Rengifo also excelled as a muralist, especially in two major works. One of the is The Myth of Amalivaca, a mosaic mural located in the Caracas Simón Bolívar Center which shows the creation of the world in the Caribe people’s worldview. The other one (also mosaic), located in the Paseo Los Próceres (Caracas), is the three panel work Creators of our Nationality, dedicated to the epic independence struggle.

Culture and struggle

Beyond depicting Venezuelan reality in his visual artwork, Rengifo also reflected and wrote on the role of artists and intellectuals.

The oil bonanza and the rentier culture deepened inequalities and created a parasitic bourgeoisie, with imported consumer habits and always looking towards the outside. This vision ended up reflected on a generation of artists defending art for art’s sake, aesthetics (also foreign) as a goal in itself, and looking for recognition abroad.

César Rengifo was very critical of this perspective that saw art and culture as disconnected from the country’s social reality. For example, in an essay titled Venezuelan social life and art, he wrote:

Rengifo also made a point of analyzing the evolution of Venezuelan culture as a function of the reigning economic model. In particular, in The agrarian question and our cultural process, he explained how the latifundio model, coupled with oil exploration, led to a massive rural exodus. This phenomenon in turn put a halt to cultural expressions rooted in indigenous resistance to colonization and the independence struggle.

«This complex set of causes is playing a part in the daily and growing disintegration of the Venezuelan cultural process,» he wrote in this essay. The flip side is the imposition of a standardized culture which does not reach the majority of the people and the importing of artistic currents such as impressionism and abstractionism.

But Rengifo’s tone is not despondent and he set his sights on the land as being a fundamental issue.

The people write their own history

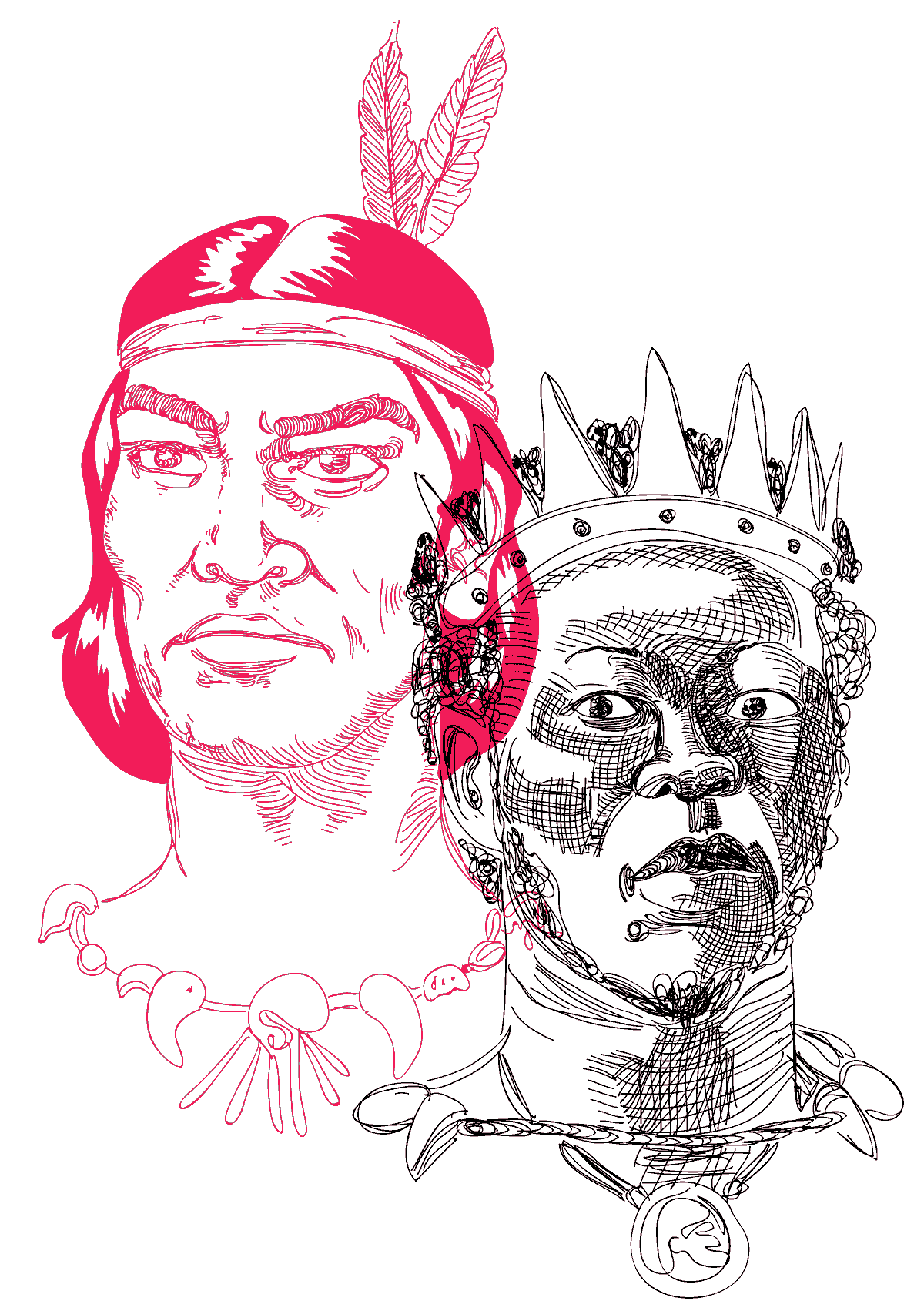

Rengifo wrote in different styles, but he is nevertheless more recognized as a playwright, and especially for his historical theater plays. These are roughly divided into four main cycles: indigenous resistance, the independence struggle, the Federal War and the oil era in the XX century.

Whereas in Shakespeare’s historical theater Richard III and Henry Tudor are main characters, the same does not hold for [independence hero] Simón Bolívar and [XIX century revolutionary leader] Ezequiel Zamora. Their historical presence is felt, but the protagonists are ordinary people. Those who put the wheels of history in motion but seldom get to write it.

For example, The Ear Sown in Carabobo («Esa Espiga Sembrada en Carabobo«) is a cantata paying tribute to the decisive battle victory in the independence war. In the play, Rengifo calls upon a series of heroes from Venezuelan liberation struggles, like [indigenous chief] Guaicaipuro or [slave rebellion leader] Negro Miguel, during the burial of an unknown soldier killed in the Battle of Carabobo.

In so doing, Rengifo ties together all the liberation struggles, but honoring those who gave their lives for the country without any fame or recognition. Bolívar makes an appearance at the very end, with a voice stressing that the «ear sown in Carabobo» will live forever, and calling for its seeds to be sown everywhere.

Similarly, the play A Certain Ezequiel Zamora («Un Tal Ezequiel Zamora») takes place during the XIX century Federal War. A humble family from rural Barinas State tries at all costs to stay away from the fighting. On one hand they want to stop their sons from being drafted, and on the other they feel the war is a mere struggle between elites. But the war, with its devastating effects, inevitably shows up on their doorstep.

In the end, the father recognizes that there is no choice but to fight for justice and dignity, and closes with the following words:

Rengifo resisted the the urge to produce a caricature of an epic people. In contrast, his characters are real, with dreams and fears, selfishness and bravery. However, it is always clear which way the winds of history blow, as is Rengifo’s position in the (class) struggle.

The Caracas-born playwright left behind a vast and diverse legacy which remains as relevant as ever. From his critical perspectives on the capitalist rentier model to his efforts to have the people tell their own tale, as well as his debates on the role of art and culture, César Rengifo remains an artist and intellectual prototype, with deep roots and commitment to popular struggles.

Research and text: Ricardo Vaz. Artwork: Valentina Aguirre. Proofreading: América Rodríguez.