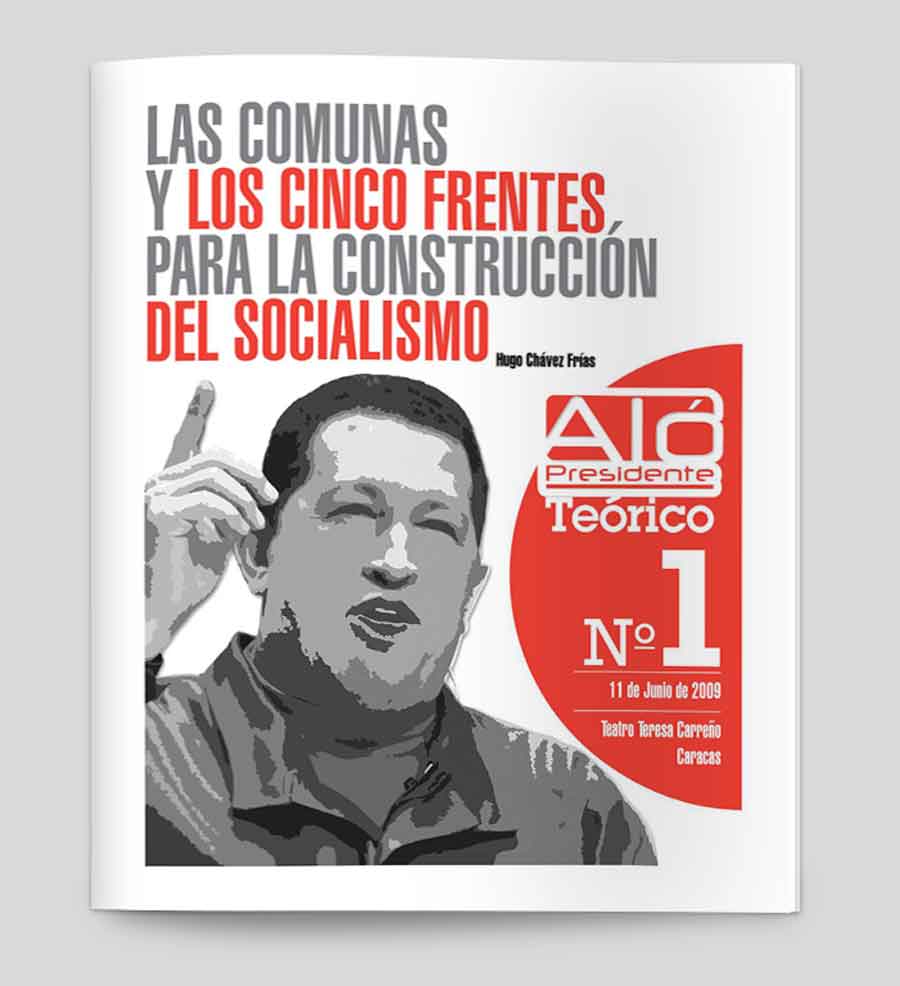

“I was told we only have one hour. Do you think it’s possible?” With these words, the remarkable first episode of the Aló Presidente Teórico got underway 12 years ago. Knowing Hugo Chávez, it was naturally impossible for the broadcast to take just one hour.

Aló Presidente Teórico #1 stands as one of the Bolivarian Revolution’s most important theoretical references. It is not a book or a pamphlet, but a four-hour televised broadcast with over two thousand people. On June 11, 2009, Chávez introduced into the national debate the key ingredient in the Venezuelan path towards socialism: the commune.

‘Giving birth’ to socialism

“It’s impossible to have a revolution without revolutionary theory, that’s what Aló Presidente Teórico is about.”

This is how Chávez summed up the show’s goal. In the first episode alone, Bolívar, Marx, Mészáros and Mariátegui were a few of the references brought up.

The six-episode broadcast series, and the first one in particular was an opportunity to define concepts, add new elements to debate, link theoretical ideas to concrete popular experiences, tear apart traditions inherent to capitalism, all alongside a constant exercise of self-criticism.

The former Venezuelan president highlighted the “creative flexibility” that should be the mark of all revolutions, calling for a balance between building something new and drawing from past experiences, such as the commune in the Chinese Revolution. It was the moment to take the leap towards a higher form of popular organization, to “give birth” to socialism from the communes.

In this inaugural broadcast, Chávez dwelled on two important and symmetrical warnings. On one hand, he stressed that the communes would not be the work of the presidency or any other institution but a creation of the masses. He urged communards to take ownership of their popular governments, territories and means of production, and to never become the tail of government bodies or political parties. The commune belonged to the people.

On the other hand, he insisted that all state institutions should place communes front and center in discourse and practice, as opposed to thinking they were someone else’s problem. “Wherever the revolutionary government goes to set up a new socialist project, it needs to boost and help build the commune,” he said.

Chávez would come back to this point very strongly in his last public address, “Strike at the Helm” (October 20, 2012). He repeatedly asked his ministers “where is the commune?” and concluding with an impassioned cry of “commune or nothing!”

The nation’s new body

Participatory and protagonist democracy, a central tenet of the Bolivarian Process, was written into the 1999 Constitution. After that, different popular organization efforts finally took shape in the form of communal councils, with their legal basis set in the 2009 Organic Law of Communal Councils and the 2010 Organic Law of Communes.

In Aló Presidente Teórico #1, Chávez called for communal councils (nuclei) to come together and form communes (cells) according to their social and territorial reality. The communes would then take control of the local means of production in order to self-manage the needs and projects of their communities without submitting to outside political and territorial control.

According to Chávez, these self-government cells faced five main battlefronts: moral, social, political, economic and territorial.

The televised program did not allow for detailed discussion of every issue, but it did lay down guiding principles such as the need to consolidate social property. Equally important, in Chávez’s vision, was going beyond local dynamics, weaving communes together to build a unified national system in the mid to long term. Quoting essayist Antonio Aponte, the president emphasized raising political, social, economic and organizational relations from the grassroots to the national scale.

“This is the nation’s new body, built from below, from the communes.”

Progress and challenges for the communes

Between 2010 and 2012, 50 communes were registered and 214 were “under construction.” In 2013 there were 350 active communes. Nowadays, according to official figures, the country has 3,278 registered communes and a further 970 under construction.

Chávez’s call to multiply and empower communes has faced several challenges and contradictions. The economic crisis and US sanctions have undoubtedly hampered the process. Nevertheless, the communal project is still alive.

El Maizal Commune stands out as an example of this leap towards popular self-government. In Aló Presidente Teórico #1, El Maizal’s young spokesman, Ángel Prado, showed how the commune was breaking the old political-territorial barriers by spanning in both Lara and Portuguesa states.

In the 12 years since, El Maizal has become a reference for popular power recognized in Venezuela and abroad alongside several others such as El Panal 2021 Commune (Caracas) or the Che Guevara Commune (Mérida). Amidst all the difficulties, these experiments have continued on their path of invention to uphold the socialist horizon.

Nowadays, several communes and other grassroots organizations are pushing the Communard Union. The up and coming project looks to build what Chávez proposed 12 years ago: a unified national system of communes.

Revolutionary communication

The Aló Presidente broadcasts were one of the Bolivarian Revolution’s most extraordinary initiatives and one of the “secrets” of its popularity. In 378 episodes, Chávez set up a direct dialogue with the people without the biased mediation of traditional media. With plenty of debate and (self-)criticism, Venezuelans became actors, their voices heard loud and clear. Never again would they be mere spectators.

“We won’t fail history, nor the future.”

The theoretical edition of the broadcast was another step in the construction of a socialist project that would conform to Venezuelan reality. As such, the historic leader of the Revolution saw the need to expand the theoretical basis on which the new socialist society was to be built. The commune would not be the work of an enlightened vanguard but a true creation of the masses.

Another lasting imprint from Aló Presidente Teórico #1 is the atmosphere in which it took place, alongside an enthusiastic people eager to take destiny in their own hands. Choosing a random moment of the broadcast, there is a good chance to find Chávez laughing. His charisma and ability to relate with the people through down-to-earth stories (without ever losing his thread) go a long way towards explaining how dearly he was held. But this lightness is also a reminder that revolution is not just about sacrifice and discipline, it is also about solidarity, joy and, above all, love.

The symbolic broadcast firmly established the commune in the Bolivarian Process and laid out the road towards the Communal State, towards socialism. With contradictions, progress and setbacks like any other transformative project, popular power remains the beating heart of revolutionary potential in Venezuela. The struggle continues. Commune or nothing!

Text: Ricardo Vaz. Research: Andreína Chávez y Ricardo Vaz. Cover illustration: Eduardo Cárcamo. Artwork: Kael Abello.